Computer Systems

Summary

Summary

Table of Contents

- Layered Network Models

- HTTP

- FTP - File Transfer Protocol

- SMTP - Simple Mail Transfer Protocol

- DNS - Domain Name System

- Sockets

- UDP User Datagram Protocol

- TCP Transport Control Protocol

- Network Layer

- Subnets

- Network Address Translation (NAT)

- Fragmentation

- Routing

- IP Multicasting

- Congestion Control

- Internet Control Protocols

- Layer 2

- Operating Systems Fundamentals

- Processes

- Threads

- Process Communication

- Process Scheduling

- Memory Management

- Goal

- AES: Advanced Encryption Standard

- Public Key Cryptography

- Digital Signatures

- Management of Public Keys

- Secure Communication

- System Security

- Future Computer Systems

Networks

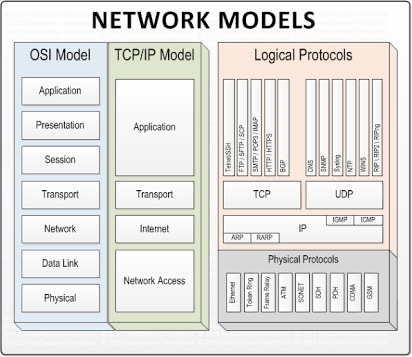

Layered Network Models

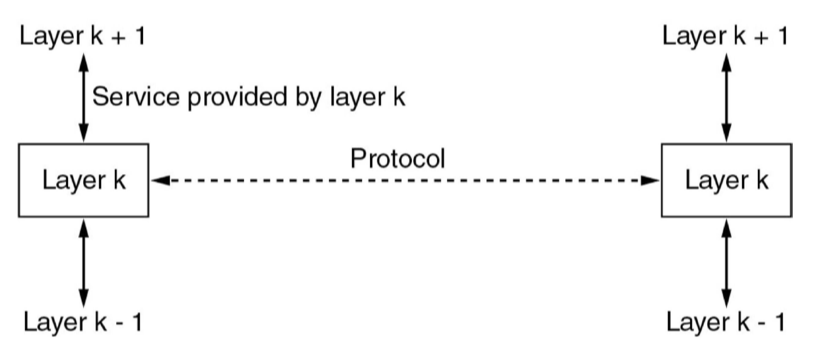

- useful to model network as stack of layers, where each layer offers services to

the layer above, and protocols govern inter-layer exchanges

- service: set of primitives a layer provides to a layer above it

- protocol: rules governing format/meaning of packets exchanged by peers within a layer

- benefits of model

- interoperability: open, non-proprietary protocols

- simplify design process with well-defined system boundaries: you can rely on services of lower layers and don’t need to implement them yourself

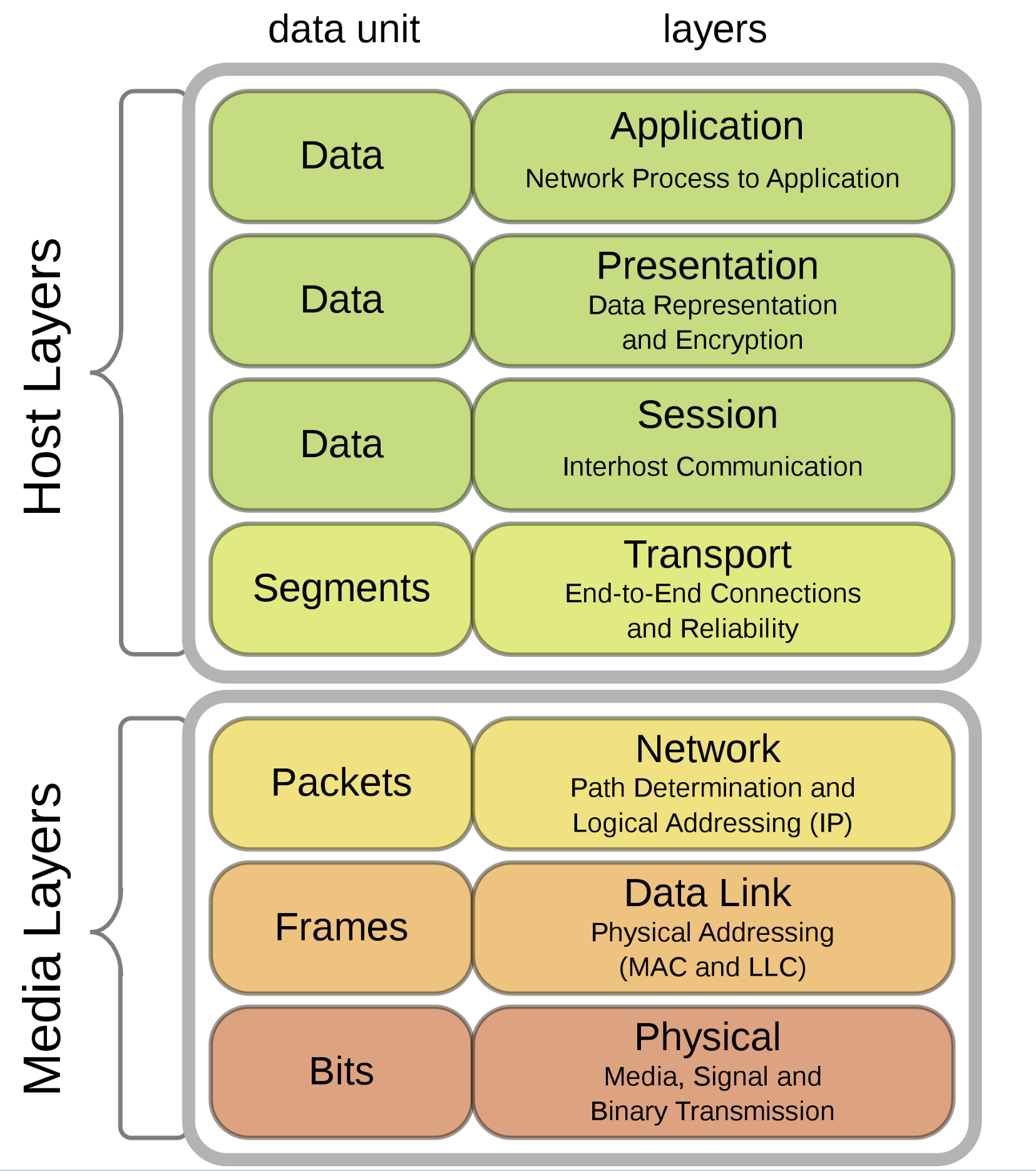

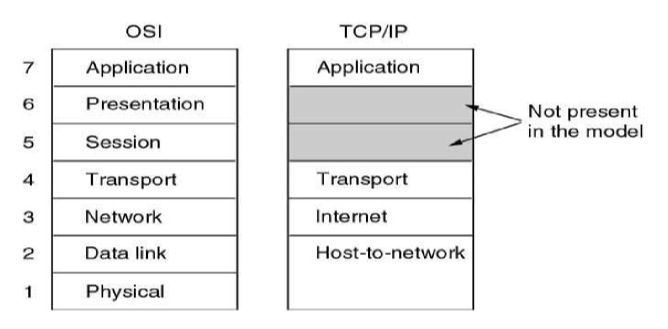

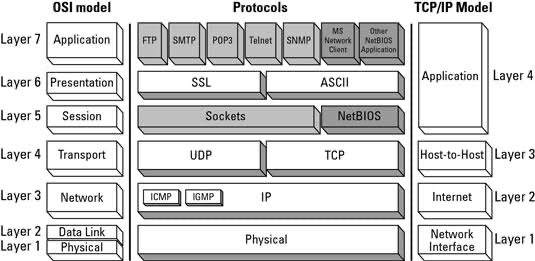

- OSI 7-layer model: standardised before implementation but not widely implemented

- useful abstraction for designing network/diagnosing faults

- TCP/IP: effectively standardised after implementation

- reflects what happens on internet

- protocol stack

Presentation layer

- OSI layer 6, providing:

- encryption

- compression

- data conversion: e.g. CR/LF to LF

- mapping between character sets

- these services are implemented by applications

- IETF considers these application layer:

- protocol to negotiate encryption is simple and separate from algorithms

- there aren’t simple common services applicable to all applications

- application is not in the kernel, making it more flexible

- RTP: Real Time Protocol

- closest thing to presentation layer

Session Layer

- OSI layer 5, providing

- authentication

- authorisation

- session restoration: e.g. continue failed download, log back in to same point in online purchase

- e.g.

- RPC: Remote Procedure Call

- PPTP: Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol

- PAP/EAP: Password/Extensible Authentication Protocol

- often used between protocols called layer 2/layer 3

HTTP

- web pages mostly base HTML file + several referenced objects

URL - Uniform Resource Locator

scheme:[//[user[:password]@]host[:port][/path][?query][#fragment]

- fragment: hint for displaying file, e.g. section header

e.g. abc://username:password@example.com:123/path/data?key=value#fragid1

Persistent connection

- HTTP 1.0 uses non-persistent connections: for each GET request a connection is established and torn down

- HTTP 1.1 introduced persistent connections, additional headers

- HTTP2 additional speed improvements

Response Codes

- 2xx: success

- 3xx: redirection

- 4xx: client error

- 5xx: server error

Cookies

- HTTP is stateless protocol

- cookies store small amount of information on user’s computer

- allows you to maintain state at sender/receiver across multiple transactions

- e.g. user ID for shopping site

FTP - File Transfer Protocol

- uses two parallel TCP connections to transfer files

- control connection: persistent

- data connection: non-persistent

SMTP - Simple Mail Transfer Protocol

- transfer messages from sender’s computer or mail server to recipient’s mail server

- can use persistent TCP connections between mail servers

- messages can take multiple hops

Comparison HTTP vs SMTP

- HTTP: transfers objects from Web server to Web client (usually browser)

- SMTP: transfers messages from mail server to mail server

- HTTP: primarily pull protocol; i.e. requesting content from a server

- SMTP: primarily push protocol; i.e. sending content to another server

- SMTP messages are ASCII only; HTTP messages are not

- HTTP encapsulates each object in single message; SMTP combines all message objects into a single message

DNS - Domain Name System

- map human readable names to other things

- UDP, port 53

- TCP would require substantial overhead: setting up/maintaining/tearing down connections. Wouldn’t scale well

- don’t need reliable transfer: if a packet gets lost, resend it with no ill effects

Database: Resource Records

- resource records carried by DNS replies

- 4-tuple:

(Name, Value, Type, TTL)

- 4-tuple:

| Type | Value |

|---|---|

| A | IPv4 address for hostname Name |

| AAAA | IPv6 address for hostname Name |

| NS | Hostname of authoritative DNS server for domain Name |

| CNAME | Canonical hostname for alias hostname Name |

| MX | Mail exchange. Canonical name of a mail server. Allows company to have same aliased name for mail and Web |

- Authoritative DNS server for a particular hostname contains corresponding A record

- Non-authoritative server for a given hostname: contains a NS record for domain that includes the hostname

- also contains A record that provides IP address of the DNS server referenced in the NS record

- Can use multiple A records for a single domain name to balance traffic across multiple servers

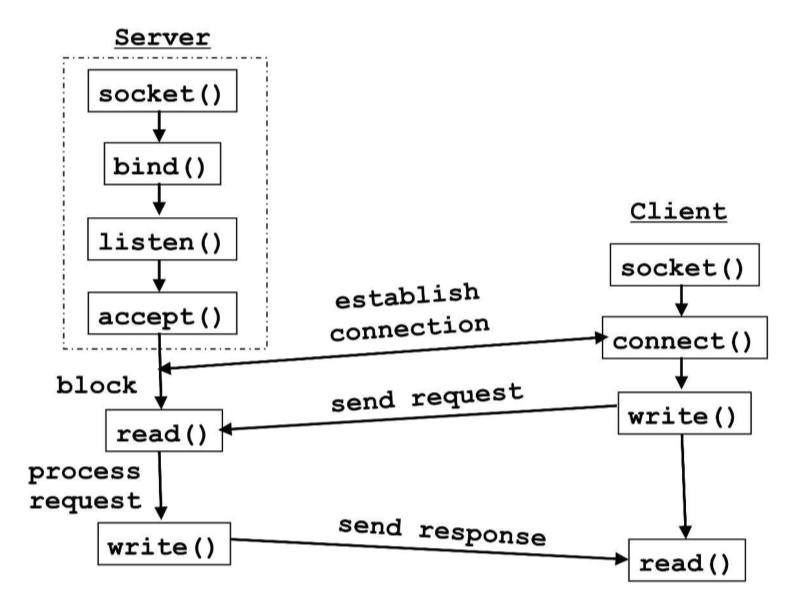

Sockets

- transport layer protocols provide multiplexing/demultiplexing service

- socket: interface between application and transport layer implementation of

the kernel, allowing application processes to receive and send data

- each socket has a unique identifier

- UDP:

([protocol,] destination IP addr, destination port) - TCP:

([protocol,] source IP addr, source port, dest IP addr, dest port)

- UDP:

- each socket has a unique identifier

- multiplexing: combining multiple streams into a single stream

- gather data chunks at source host from different sockets

- encapsulate each chunk with header that will be used to demultiplex later, creating segments

- pass segments to transport layer

- demultiplexing: examine fields in segment to identify receiving socket and direct segment to that socket

Sockets in C

int listenfd = 0, connfd = 0 // listen, connection file descriptors

char sendBuff[1025]; // send buffer

struct sockaddr_in serv_addr;

//create socket

listenfd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

// initialise server address

memset(&serv_addr, '0', sizeof(serv_addr));

// initialise send buffer

memset(sendBuff, '0', sizeof(sendBuff));

// type of address: Internet IP

serv_addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

// listen on any IP address

serv_addr.sin_addr.s_addr = htonl(INADDR_ANY);

// listen on port 5000

serv_addr.sin_port = htons(5000);

// bind

bind(listenfd, (struct sockaddr*)&serv_addr, sizeof(serv_addr));

// listen: maximum number of client connections to queue

listen(listenfd, 10);

// accept

connfd = accept(listenfd, (struct sockaddr*)NULL, NULL);

// write

snprintf(sendBuff, sizeof(sendBuff), "Hello World!");

write(connfd, sendBuff, strlen(sendBuff));

// close

close(connfd);

// connect

connect(connfd, (struct sockaddr *)&serv_addr, sizeof(serv_addr));

// receive

while ((n = read(connfd, recvBuf, sizeof(recvBuff)-1) > 0) {

// process buffer

}

UDP User Datagram Protocol

- lightweight: provides multiplexing/demultiplexing and light error checking

- connectionless

- unreliable: no guarantee on delivery, order, integrity

- poor choice for non-idempotent operations

TCP Transport Control Protocol

- see TCP notes

- provides flow control to prevent sender overflowing receiver’s buffer

- sliding window protocol

- maintained by receiver, remaining space communicated to sender

- provides congestion control: sender adjusts transmission rate according to implicit

congestion state of network

- maintain congestion window

- perceive network congestion: segment loss via timeout, triple DupACK causing fast retransmission

Network Layer

- role: get data from source to destination

- route traffic efficiently

- nodes must be given addresses

- internet: network of network

- internet layer: sublayer atop network layer

- source and destination may be in different network

- hop is a whole network

- runs on routers

- store-and-forward packet switching: packets are stored in routers until it has fully arrived and the checksum has been checked, before forwarding it on to the next router

Connectionless

- packets are injected into network individually and routed independently of each other

- no advance setup needed

- packet switching: IP

- minimum required service: send packet

- datagram network

- forwarding table: pair of destination and outgoing line to use for that destination

- each packet carries a destination IP address used by routers to individually forward each packet

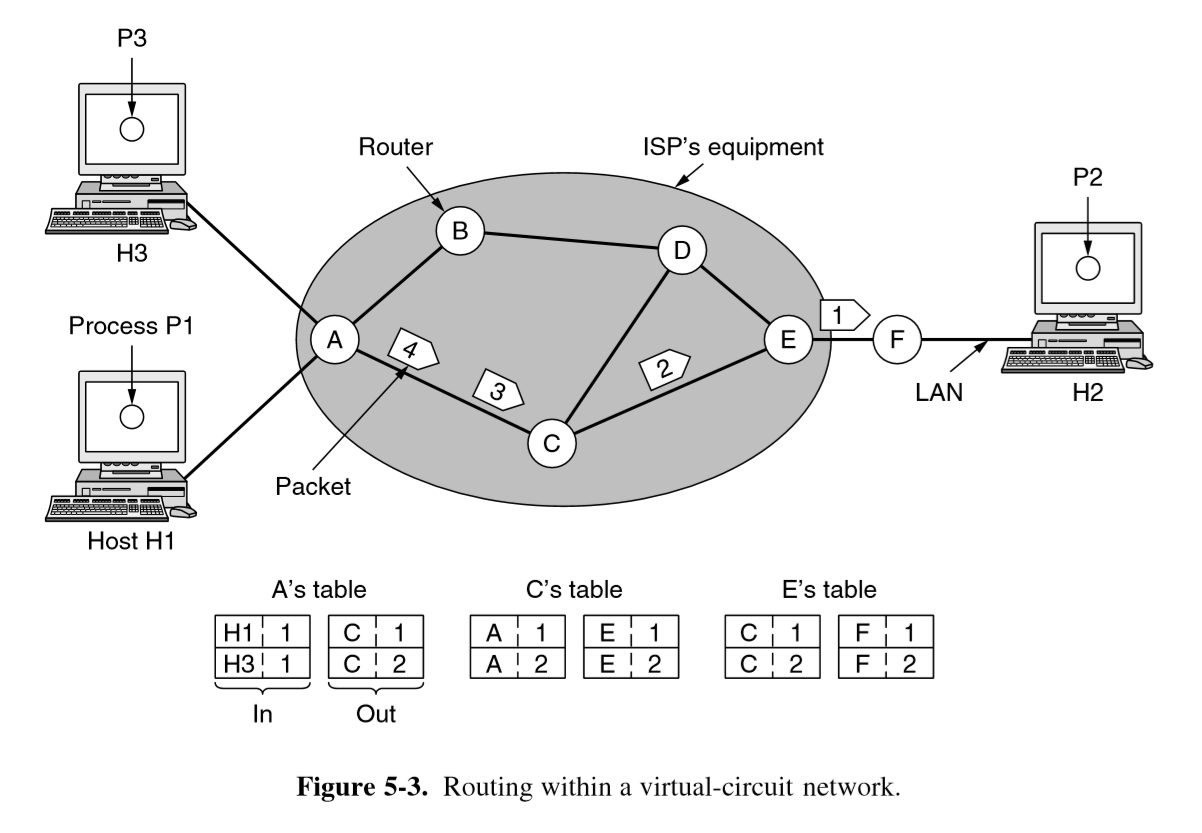

Connection oriented

- path from source router to destination must be established before packets can be sent

- virtual circuit switching, analogous to physical circuit switching of telephones

- idea: avoid having to choose a new route for every packet sent: route from source to destination is chosen as part of connection setup and stored in router tables. This route is used for all traffic flowing over the connection. Once connection is released, virtual circuit is terminated

- each packet carries an identifier of the virtual circuit

- MPLS: MultiProtocol Label Switching: used within ISP networks in the Internet

with IP packets wrapped in MPLS header, 20-bit connection identifier

- network layer below internet sublayer

- often hidden from customers

- ISP establishes long-term connections for large amounts of traffic

- used when QoS is important:

- prioritise traffic

- service level agreements for network performance

- reliable connectivity with known parameters

- expensive: 20-100x per Mbps than standard connection

- act as single link of IP network

- forwarding table has mapping between:

- Incoming: (source host, connection ID)

- Outgoing: (destination host, connection ID)

Comparison: Virtual Circuit vs Datagram Networks

| Issue | Datagram Network | Virtual-circuit network |

|---|---|---|

| Circuit setup | Not needed | Required |

| Addressing | Each packet contains full source/dest address | Each packet contains short VC number |

| State information | Routers don’t hold state info about connections | Each VC requires router table space per connection |

| Routing | Packets routed independently | Route chosen when VC set-up, all packets follow it |

| Effect of router failure | None, except packets lost during crash | All VCs through the failed route are terminated |

| QoS / Congestion control | Difficult | Easy if resources can be allocated in advance for each VC |

- datagram network has no overhead with connection setup but each packet has more overhead with addressing

- for long-running uses e.g. VPN between corporate offices, permanent VCs may be useful

Quality of Service

- some services are important or aren’t robust to network delay

- VoIP vs file downloads

- VPN connections vs web browsing

- within network or autonomous system, services can be prioritised

- explicit: can be done if you own the network using Differentiated Services Header to define class of traffic

- implicit: used on shared network, ISP traffic shaping

Internet protocol

- guiding principles

- working OK is better than ideal standard in progress

- keep it simple

- be strict when sending, tolerant when receiving

- make clear choices

- negotiate options at runtime

- consider scalability

- best effort not guaranteed performance

- responsible for moving packets through various networks from source to destination host

- IP address reflects interfaces, not hosts: multiple network cards means multiple IP addresses

Types of Address

- unicast: one destination, normal address

- broadcast: send to everyone

- multicast: send to a particular set of nodes; e.g. live streaming

- anycast: send to any one of a set of addresses; e.g. used for DNS, NTP

- geocast: send to all users in geographic area; e.g. emergency warning

IPv4 Address Classes and CIDR

- original IP addresses were based on classes to simplify routing by examining only

the prefix

- wasteful: networks often much larger than needed

- Classless InterDomain Routing: each interface/route explicitly specifies which bits

are the network field

- network in top bits, host in bottom bits

- network corresponds to contiguous block of IP address space, a prefix

Network = network mask & IP address- efficient routing: intermediate routers only maintain routes for prefixes, not every individual host

- only when packet arrives at destination network does host portion need to be read

- route aggregation: performed automatically, greatly reducing size of routing table

- in case of overlapping prefixes, choose the longest matching prefix (most specific)

IPv6

- designed to address exhaustion of IPv4 address space

- additional changes

- simplify header: faster processing

- improve security: has been back-ported to IPv4

- more QoS support

IPv6 Address

- IPv6 address: 128 bits

- 8 hextets (4 hexadecimal digits) separated by

: - 128 bits (16 bytes)

- abbreviation:

- leading 0s from any group is removed (all/none)

- consecutive hextets of 0s replaced with

::. Can only be used once in an address, otherwise would be indeterminate

- backwards compatible with IPv4:

::ffff:192.31.2.46

Consider 2001:0db8:0000:0000:0000:ff00:0042:8329

Removing leading zeros: 2001:db8:0:0:0:ff00:42:8329

Use double colon: 2001:db8::ff00:42:8329

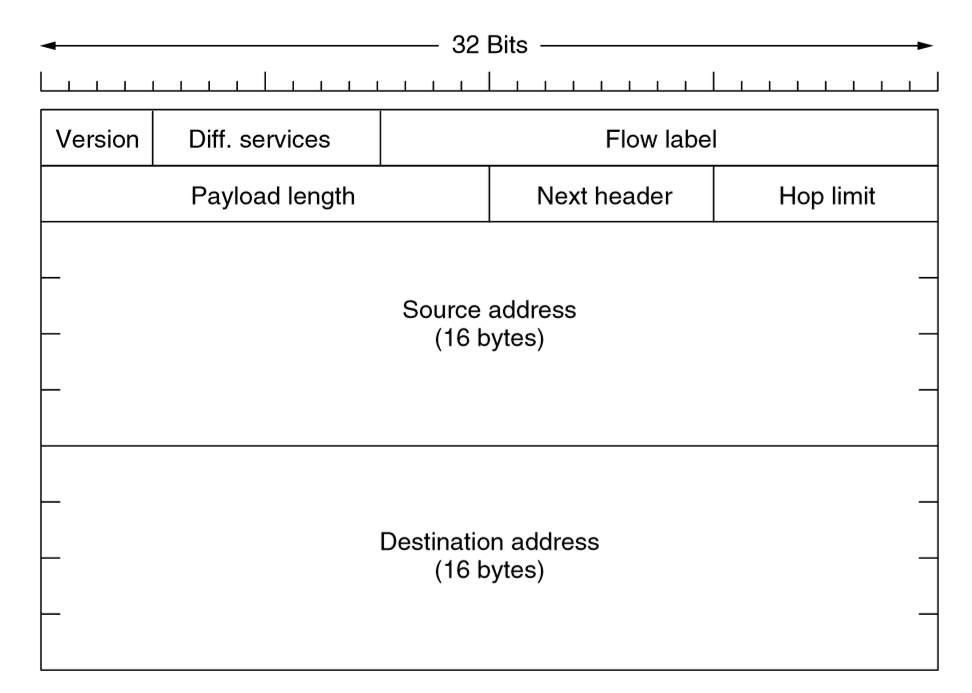

IPv6 Header

- Version: 6 for IPv6

- Differentiated services: QoS

- Flow label: provides way for source/dest to mark groups of packets having the same

requirements, such that they should be treated the same way by the network

- pseudoconnection

- attempt to have flexibility of datagram network with guarantees of virtual-circuits

- Payload length: NB data only, c.f. IPv4 Total length (inclusive of header)

- Next header: indicates which (if any) optional extension header follows

- if this is the last IP header this field is used for transport protocol (TCP, UDP)

- Hop limit: prevent packets living forever, same as TTL in IPv4

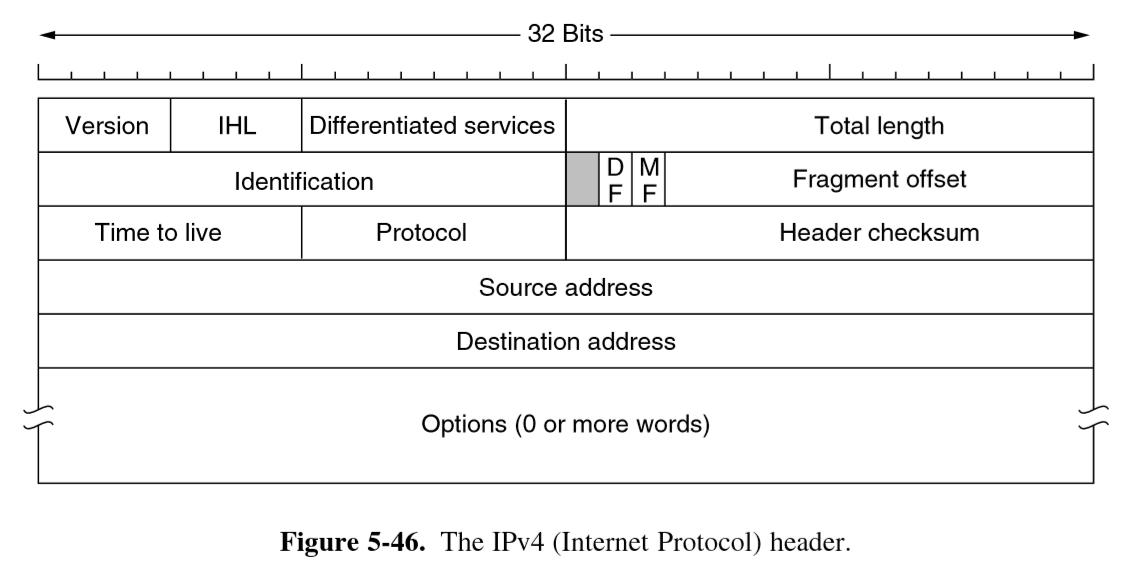

IPv4 header

- header is variable length: Options

- total length: includes header + data. Maximum = 65535 bytes

- checksum: add up 16-bit halfwords of header with one’s complement arithmetic, then

one’s complement the result. detect errors as packet travels through the network

- must be recomputed at each hop as at least one field always changes (TTL)

Subnets

- subnetting: splitting up network into several parts internally within an organisation

while acting externally as a single network

- splits can be unequal but need to share a common prefix

- future changes can be made with no external impact (e.g. additional IP allocation)

- hierarchical: ISP allocates subnets to organisations; no real distinction between network/subnet

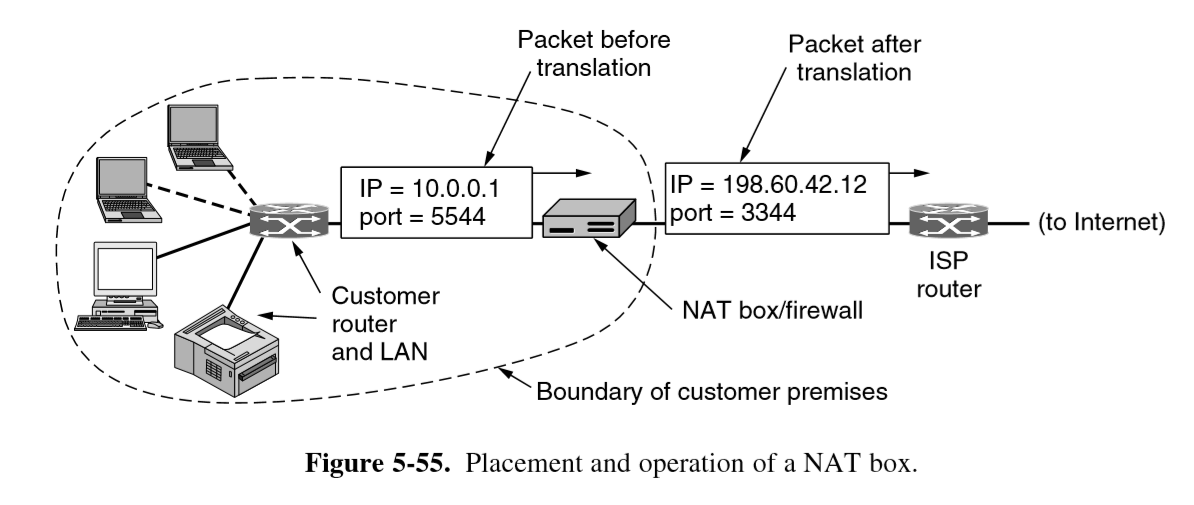

Network Address Translation (NAT)

- method to handle greater number of clients than IPv4 address space would allow

- ISP assigns individual home/business single IP address for Internet traffic

- within customer network, every computer gets a unique internal IP address

- when packets need to exit the customer network they undergo address translation by the NAT box. This rips out the internal IP address and replaces it with the external IP address

- NAT maintains a translation table, which replaces TCP source port

- entry: private IP, private source port, public source port

- IP, TCP checksums are recomputed

- packets arriving from outside the network are able to be looked up and directed to the correct host (after updating headers and recomputing checksums)

- widely used, significant security advantage: packets can only be received once outgoing connection established. Shields from attack

- holes need to be poked in NAT to allow, say external access to a web server behind NAT box

Private address ranges used:

- 10.0.0.0-10.255.255.255.255

- 172.16.0.0-172.31.255.255

- 192.168.0.0-192.168.255.255

NAT Criticisms

- violates IP architectural model: every interface should have unique IP address

- breaks end to end connectivity

- makes internet partly connection oriented

- violates layer model: assumes nature of payload contents e.g. UDP, TCP

- limits number of outgoing connections

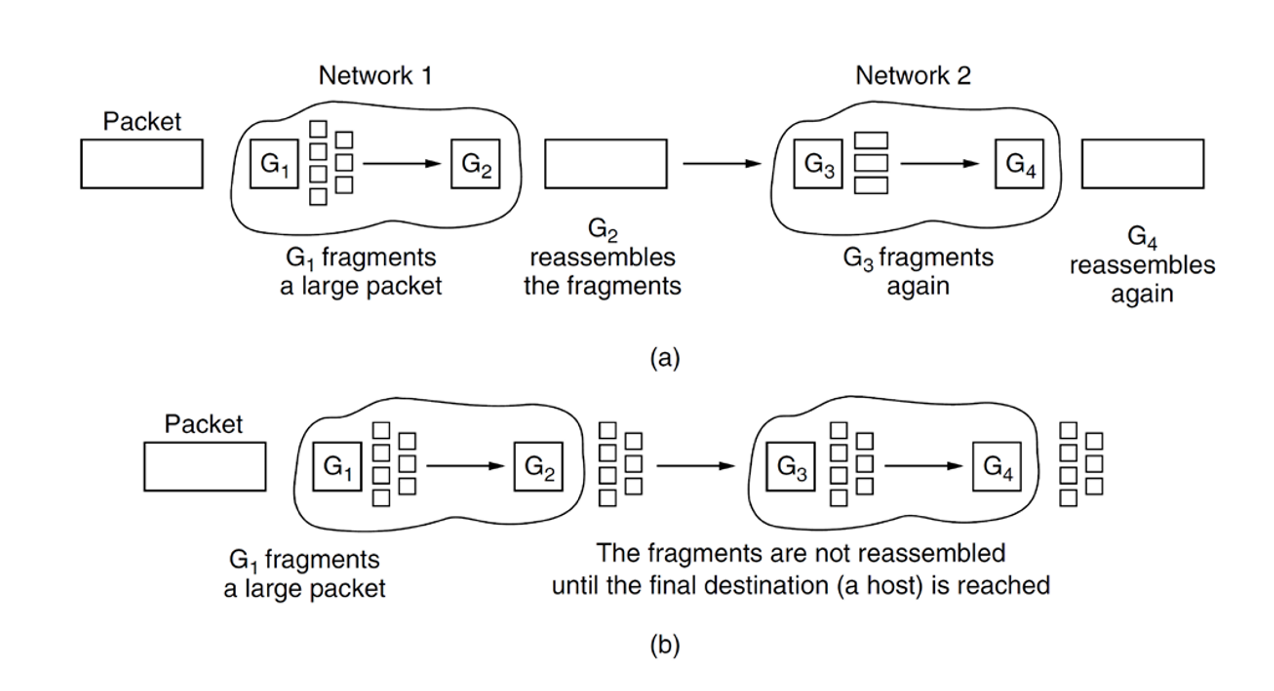

Fragmentation

- IP packets have maximum size of 65,535 bytes (16-bit total length header)

- most network links cannot handle such large sizes

- lower layer needs to be able to fragment larger packets

- motivations: hardware (buffers), OS, protocols, reduce transmission errors, increase efficiency

- hosts want to transmit large packets (reduced workload)

- common max size

- Ethernet: 1500 bytes

- WiFi: 2304 bytes

- MTU: maximum transmission unit: maximum size for that network/protocol

- Path MTU: max size for path through network, i.e. min of MTU on each link

- dynamic routing: don’t know in advance

- original solution: allow routers to break large packets into fragments

- transparent fragmentation: reassembly at next router. Subsequent routers are unaware of it

- nontransparent fragmentation: reassembly at destination host

- IP headers:

- identification: identifies packet

- DF: Don’t fragment: orders routers not to fragment packets. also part of determining path MTU

- MF: More fragments: all fragments except the last one have this set. indicates whether all fragments have arrived

- Fragment offset: where in current packet fragment belongs

- fragments are in 8 byte blocks: fragment offset must be on 8 byte boundary

- 13 bits

Downsides

- overhead: 20 byte header per fragment incurred from point of fragmentation on

- if a single fragment is lost, entire packet needs to be resent

- overhead on hosts for reassembly is high

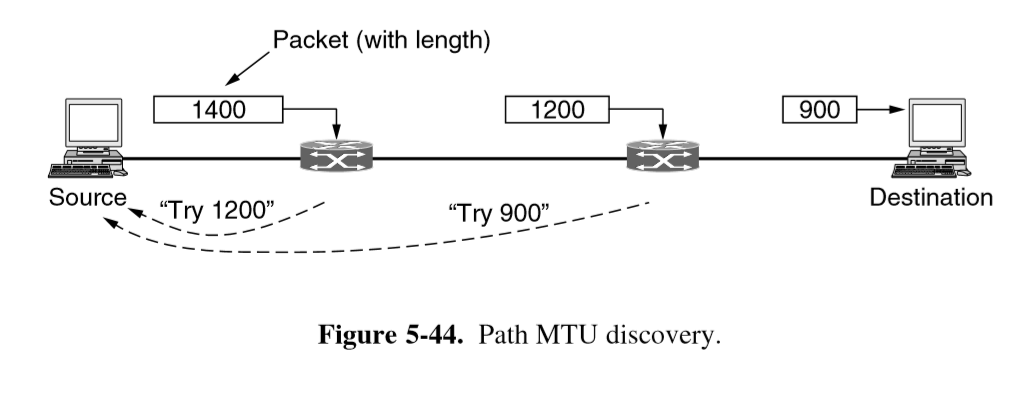

Path MTU Discovery

- packets are sent with DF bit set: if a router cannot handle the packet it sends ICMP to sender telling it to fragment packets at smaller size

IPv4 vs IPv6 fragmentation

- IPv4: either non-transparent fragmentation or path MTU discovery

- minimum accept size: 576 bytes

- IPv6: routers will not perform fragmentation. Hosts expected to discover optimal

path MTU

- minimum accept size: 1280 bytes

- ICMP messages are sometimes disallowed, causing MTU path discovery to fail

Routing

- forwarding table: maps destination addresses to outgoing interfaces

- every router has one

- on receiving a packet, router:

- inspects destination IP address in header

- indexes table

- determines outgoing interface

- forwards packet out that interface

- repeated by all routers along route to destination

- routing: applying a routing algorithm to populate forwarding table

- forwarding: using forwarding table to determine which link to place an outbound packet on

- routing algorithm: decides which output line incoming packets should be transmitted on.

Consists of:

- algorithm local to each router

- protocol to gather network information needed by the algorithm

Routing tables

- usually based around triple:

- input: destination IP address (base)

- input: subnet mask

- output: outgoing line (physical/virtual)

e.g. 203.32.8.0 255.255.255.0 Eth0

Properties of a good routing algorithm

There are many goals, often in tension:

- correctness: finds a valid route between all pairs of nodes

- simplicity

- robustness: a router crash shouldn’t require a network reboot

- stability: reach equilibrium and stay there

- fairness

- efficiency

-

flexibility to implement policies

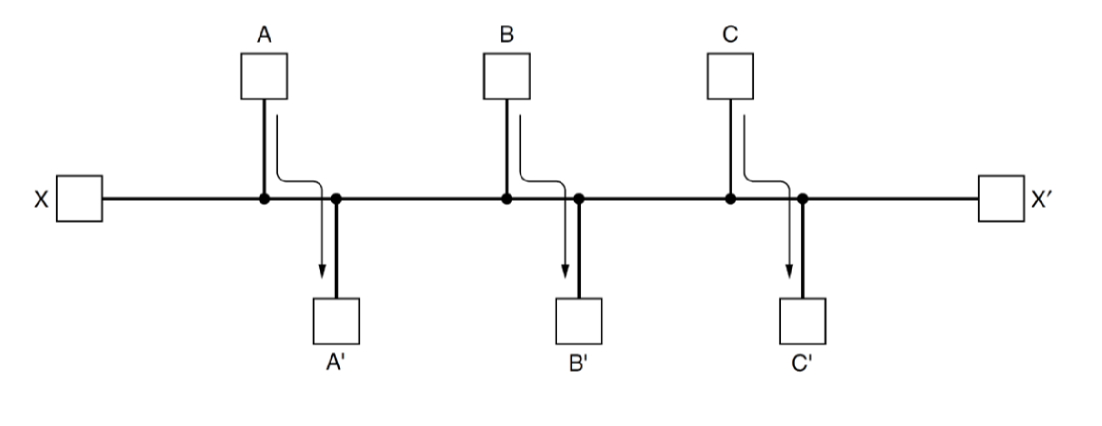

- fairness vs efficiency: if there is enough traffic from $A\rightarrow A’, B\rightarrow B’, C\rightarrow C’$

to saturate the horizontal link, what is the most efficient course of action for handling traffic $X\rightarrow Y$?

- 3x data with $A\rightarrow A’, B\rightarrow B’, C\rightarrow C’$ transmitting compared to $X\rightarrow Y$

- optimal efficiency leaves $X\rightarrow Y$ unconnected: unfair

- need to balance the two

- delay vs bandwidth: path with low delay may have narrow bandwidth

- what are you optimising: mean packet delay? max network throughput?

- simple approach:

- minimise number of hops a packet has to make: tends to reduce per packet bandwidth and improve delay

- may also reduce distance travelled but not guaranteed

- real-world implementations assign costs to each link, and look for minimum cost path

- more flexible

- still unable to express all routing preferences

Adaptive vs Non-adaptive

- non-adaptive/static routing

- doesn’t adapt to the network topology: if network changes, routing tables don’t update

- calculated offline and uploaded to the router at boot (e.g. from ISP)

- doesn’t respond to failure

- reasonable when there is a clear choice, e.g. home router: a static route out of your network is reasonable as it’s the only choice

- adaptive routing

- dynamic, adapts to changes in topology

- may adapt to traffic levels: if route depends too heavily on traffic levels it may be unstable, rarely implemented

- more susceptible to routing loops/oscillation

- optimises some property: distance, hops, …

- get information from adjacent routers or all routers in the network

Flooding

- simplest adaptive routing approach

- very aggressive: send out to everyone you can

- guarantees shortest distance and minimal delay

- useful benchmark for speed: i.e. an algorithm 1.5x slower than flooding but 100x more efficient

- robust: if there is a path, it will find it

- highly inefficient: generates huge number of duplicate packets, uses lots of bandwidth and wastes router memory

- need way to discard packets (TTL)

- if unknown, set to diameter of network: shortest path between 2 most distance nodes

- each node must keep track of packets it has forwarded

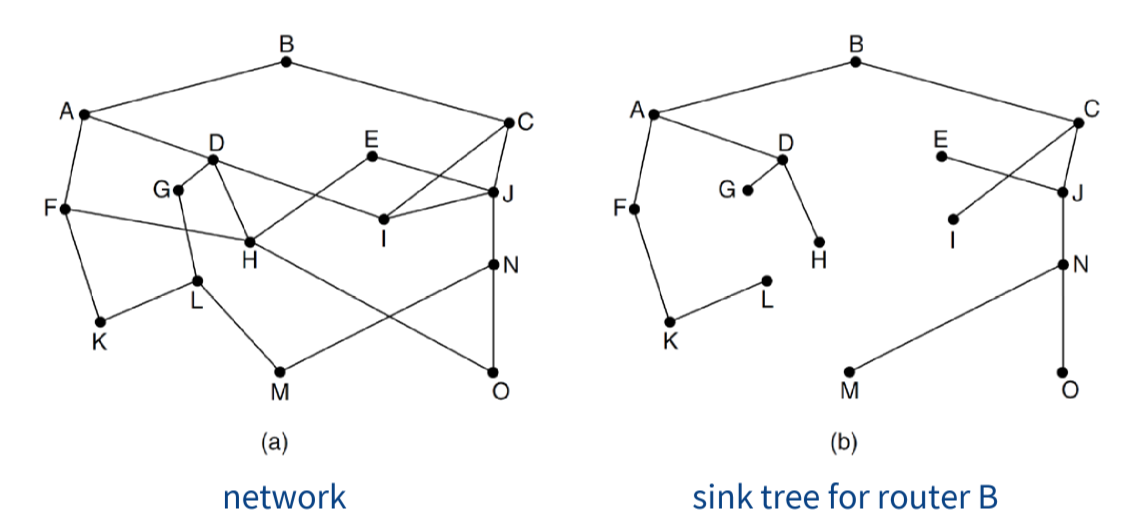

Optimality Principle

- if router $J$ is on optimal path from router $I$ to $K$, then optimal path

from $J$ to $K$ also falls along the same route

- only valid when cost/quality of route is scalar (this assumption breaks in BGP)

- implies set of optimal routes from all sources form a tree rooted at destination

Shortest Path

- e.g. Dijkstra’s: node can be in one of three states

- unseen

- open: visited neighbour of it, we know a path

- closed: have visited it

- algorithm moves unseen-open-closed

- algorithm we can apply to graph but we need a protocol to get this information

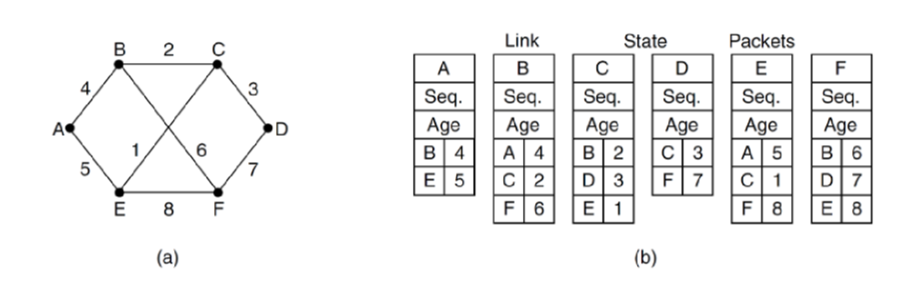

Link-State Routing

- replaced distance vector routing that had problems converging quickly

- variants of LS are basis of all common protocols

- in LS routing, network topology and all link costs are known

- each node needs to broadcast link-state packets to all other nodes in the network

- could run on Dijkstra’s

- “tell the world about your neighbours”

- centralised algorithm, distributed information sharing

Steps

Steps each router performs: share information, then run centralised algorithm

- Discover neighbours and learn network addresses

- Set distance/cost metric to each neighbour, building graph

- Construct packet containing what it has learned

- Send packet to/receive packets from all other routers

- Compute shortest path to every other router (e.g. with Dijkstra’s)

Neighbour discovery

- router on boot sends out

HELLOpacket on each interface. Router on the other end must reply with unique ID - costs can be set automatically/manually

- often use inverse of bandwidth: 1Gbps = 1, 100Mbps = 10

- could also use delay calculated with an

ECHOpacket - many networks manually choose preferred routes and look for link costs to make them the shortest: traffic engineering

Advertisement

- link state packet: ID, sequence number, age, list of neighbours, costs

- sequence number: increases each time node makes a new version of message

- easy to build packets, decided when is hard

- intervals? when changes occur?

- to send packets to all other routers, flooding is used

- reliable flooding: uses acknowledgements to guarantee every other router receives packet

- sequence number: if sequence number is not larger than one previously received, it discards it and doesn’t forward on the flood. Prevents forwarding out of date info

- issue: router crashes, sequence number restarts from 0. Looks like new info

is out of date

- solution: age field. Reduced by 1 each second. When it reaches 0, information is discarded

Distance-Vector Routing

- distributes topology, everyone then performs centralised routing

- true distributed algorithm: nodes announce distance from themselves to each destination

- c.f. announcing topology in link-state

- elegant, problems with implementation

- iterative: process continues until no more information is exchanged between neighbours

- asynchronous: does not require all nodes to operate in lockstep

- distributed: each node receives information from 1+ of directly attached neighbours, updates its state, then informs immediate neigbours

- uses Bellman-Ford equation

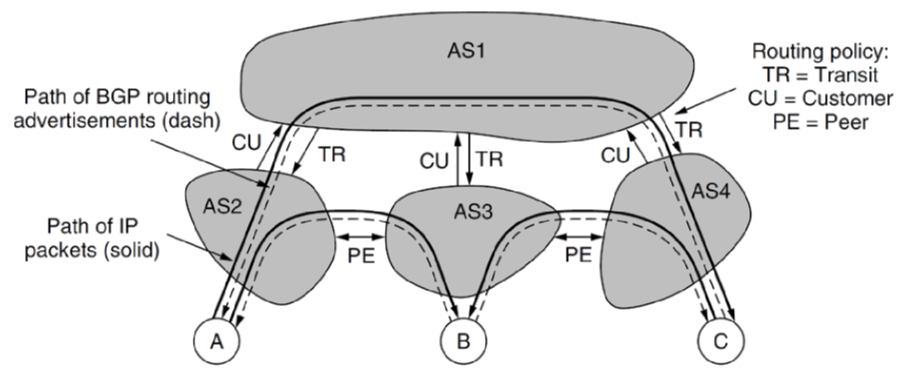

Border Gateway Protocol

- internet is constructed by internetworking independently administered networks

- autonomous system AS: collection of routers under the same administrative control

- intra-AS routing protocol: usually based on link-state, up to administrator

- e.g. OSPF: Open Shortest Path First

- inter-AS routing protocol: must be same for all ASes, BGP

- intra-AS routing protocol: usually based on link-state, up to administrator

- BGP is the protocol that glues the thousands of ISPs in the Internet together

- decentralised, asynchronous

- similar to DV

- application layer

- runs over TCP port 179 with connections between pairs of routers to exchange information

- BGP uses CIDRized prefixes representing subnets

- forwarding table entry (CIDR prefix, interface number)

- BGP provides means for each router to

- obtain prefix reachability info from neighbour AS: each subnet says “I exist and I am here”

- determine best routes to prefixes

- BGP needs to consider politics

- companies not willing to have network used by others

- ISPs not wanting to carry other ISP’s traffic

- not carrying commercial traffic on academic networks

- use one provider over another because cheaper

- don’t send traffic through certain companies/countries: security/regulation/…

- not always clear that one route is better than another: may be better in some regards, worse in others

- Bellman’s optimality principle doesn’t always apply (cost is non-scalar)

- based on: customer/provider: I pay you for transit of traffic I send/receive

- peering arrangements: we carry each others’ traffic without charge

- provider advertises routes for entire internet

- customer only advertises routes for their network to avoid transiting other traffic

- e.g. AS2 and AS3 would want to establish peering agreement so that they don’t get charged to route via AS1. But AS2 doesn’t advertise that it can reach AS1 because it doesn’t want to end up getting charged to handle AS3’s traffic

- as a result, traffic travels on valley-free routes, travelling up the hierarchy before descending

- e.g. AS2 to AS4 goes via AS1 instead of via AS3

- BGP attack: malicious AS can advertise routes for networks at very low cost, such

that traffic is re-routed through it

- 2017: Russian AS advertised routes for Google, Apple, Facebook, …

- effective way to divert traffic for monitoring or disruption

IP Multicasting

- one-to-many communication

- applications: stream live content, video conference, send update to group of machines

- class D addresses reserved for multicast

- whole group identified by single multicast IP

- to send multicast packet it is sent ot multicast IP address

224.0.0.0/24reserved on local networks (stays in LAN)224.0.0.1: all systems on a LAN225.0.0.2: all routers on a LAN

Membership

- process asks host to join/leave particular multicast IP address, host records this

- host can have multiple processes that are a part of the same group

- once no processes remain that are interested in the group, the host is no longer a member

- ~ every minute, multicast router broadcasts packet asking all hosts which multicast addresses

they are members of (using

224.0.0.1) - messages governed by Internet Group Management Protocol

Observations

- special multicast routing algorithms used to construct routing trees to deliver

messages from one sender to all receivers

- very slow, scale poorly (NP-Complete)

- not suited for huge audiences if you want optimal routing time

- huge audiences are supported, but routing will be sub-optimal

- amplification attacks: security isk

- send one ICMP echo message to multicast address

- sends lots of ICMP reply messages

- if you spoof source address you can flood spoofed address with ICMP replies

- widely deployed in organisational networks:

- Hotel TV

- Company video conferencing

- financial markets: stock tickers, data feeds

- universities: campus wide video

- generally not available to average consumer

- adds complexity to network equipment

- not proven to scale to internet size (i.e. millions of users paying for it)

- person benefiting is not the person paying for the capability

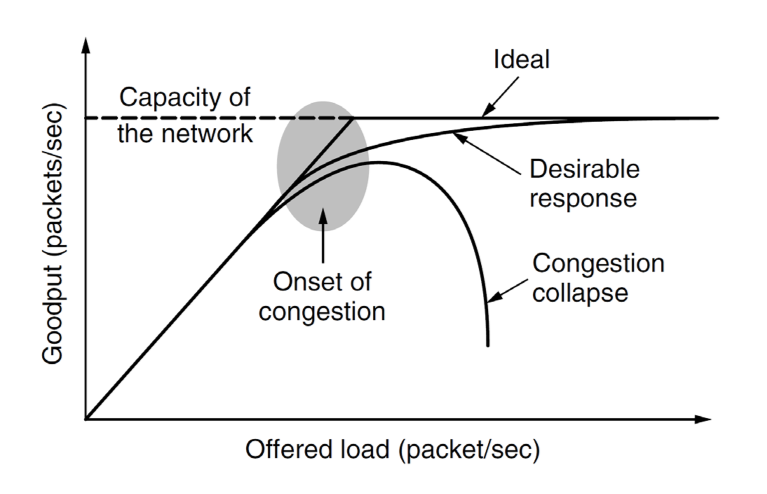

Congestion Control

- all networks have finite capacity

- too many packets on a network causes delay and ultimately packet loss, leading

to congestion collapse, when performance plummets

- packets are delayed, so they get resent, leading to more traffic

- congestion control: network problem; avoid overflowing network

- flow control: between hosts; avoid overloading receiver

- solution: slow sending rate

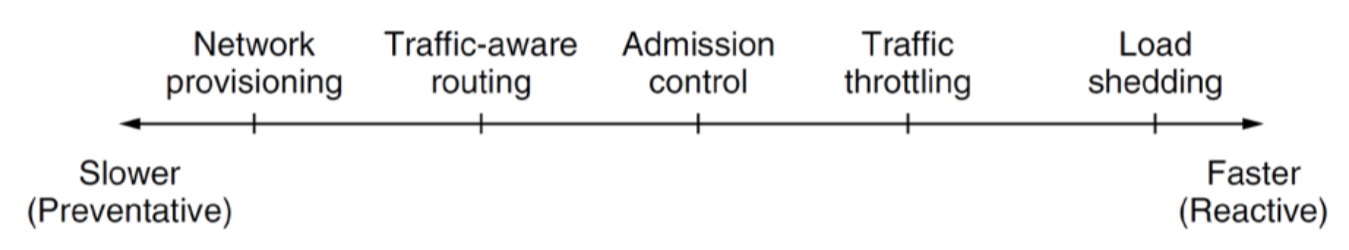

Congestion Control Solutions

Many approaches operating at different time scales

- network provisioning: build more networks

- ultimate solution: add more capacity, slow and expensive ~ months/years

- traffic-aware routing: change routing; this link is congested, so let’s bypass it

- temporary solution: eventually all routes become saturated

- works well for daily traffic patterns ~ day

- e.g. morning East to West coast, evening West to East coast

- admission control: deny access; provide engaged signal ~ mins/hrs

- used on virtual circuits to control who can place traffic onto the route

- used by MPLS

- traffic throttling: similar to TCP congestion control ~ seconds

- reduce sending rate: effective, reasonably fair

- load shedding: drop packets ~ ms/$\mu$s

- effective at solving congestion

- bad for utility of network

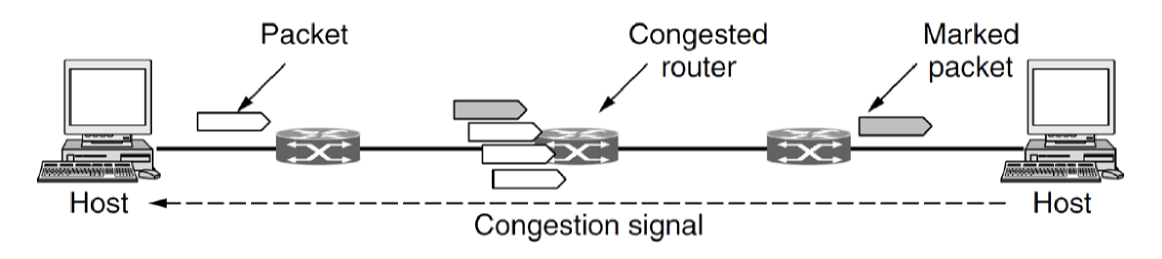

Explicit Congestion Control

- traffic throttling

- aim: congestion avoidance

- prevent reaching point of congestion collapse

- issues

- determining onset of congestion: monitor queueing delay at router

- determining which sender is causing it: need to ensure notification doesn’t create further congestion

- two least significant bits in Differentiated Services header field used for

ECN:

00: not ECN capable10or01: ECN capablej11: congestion experienced

- when receiver receives IP packet marked as experiencing congestion it echoes to the sender a TCP segment with ECE bit set (Explicit Congestion Experienced)

- sender reduces transmission rate and sets CWR (congestion window reduced) bit to acknowledge the ECE

- this only happens once per RTT, i.e. receiver sends all packets since it received ECN with the ECE bit set until it receives CWR from sender, unless CE flag is set in IP packet

- ECN closely linked to TCP: runs between Internet and Transport layers

- demonstrates blurred lines between layers in TCP/IP: tight coupling

- UDP could theoretically use ECN, but doesn’t implement it

Internet Control Protocols

- used at internet layer to manage functionality

- ICMP: internet control message protocol

- DHCP: dynamic host configuration protocol

- ARP: address resolution protocol

ICMP Internet Control Message Protocol

- used by hosts and routers to communicate network-layer information, typically used for error reporting, MTU path discovery, and network diagnostic utilities

- e.g. Destination network unreachable when web browsing originates from ICMP

- messages are carried as IP payload: architecturally lies just above IP

ping: sends ICMP echo messages- sends type 8 code 0

- receiver responds with type 0 code 0 ICMP echo reply

traceroute: exploits ICMP time exceeded message- sends out UDP segments with unlikely port number

- sends out packets to target destination each with incremented TTL (starting from 1)

- TTL hits zero at successive routers along the route, causing it to return time exceeded message, revealing IP address of router on route

- at an intermediate router when TTL hits 0, the router discards the datagram and sends ICMP warning message to the source (type 11 code 0)

- at destination, host sends port unreachable ICMP message (type 3 code 3)

- once received probe packets no longer need to be sent

- sender can now determine path and timings of route a packet will take

- messages have type and code field, and contain header and 1st 8 bytes of IP datagram that caused the ICMP message to be generated (for diagnosis)

- destination unreachable: message type used

- in path MTU discovery with fragmentation required code

- when routing algorithm is running and forwarding tables are in inconsistent state

DHCP Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol

- DHCP server automatically allocates IP addresses

-

security concerns: any device that connects will be issued an IP address

- Host sends

DHCP Discover - DHCP Server receives the request and responds with

DHCP Offercontaining available IP address, as well as network info: subnet mask, default gateway, DNS server, time servers- IP addresses issued on a lease

MAC (Medium Access Control) Addresses

- layer 2: Wired ethernet, WiFi, Bluetooth

- globally unique identifier for the interface assigned by the manufacturer

- 48 to 64 bits long

- addressing used at host-to-network/data link layer

- physical address

ARP Address Resolution Protocol

- ARP maps IP address to MAC address

- translates addresses between internet layer and physical network layer

- Broadcasts Ethernet packet asking who owns target IP address on broadcast

address

FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF - Broadcast arrives at every host on the network. The owner responds with its MAC address

- simple, not efficient

- security nightmare:

- no authentication

- caching of responses

- ARP spoofing is gateway for most MITM attacks

- way of intercepting and spoofing ARP messages to associate attacker’s MAC with another hosts IP address

Layer 2

- what IP runs over

- modern ethernet is like IP, but routers are called switches

- old ethernet like WiFi:

- shared medium: cannot choose between output ports

- broadcast a packet, it may collide, in which can you both retransmit

- mechanisms to reduce collisions: medium access control

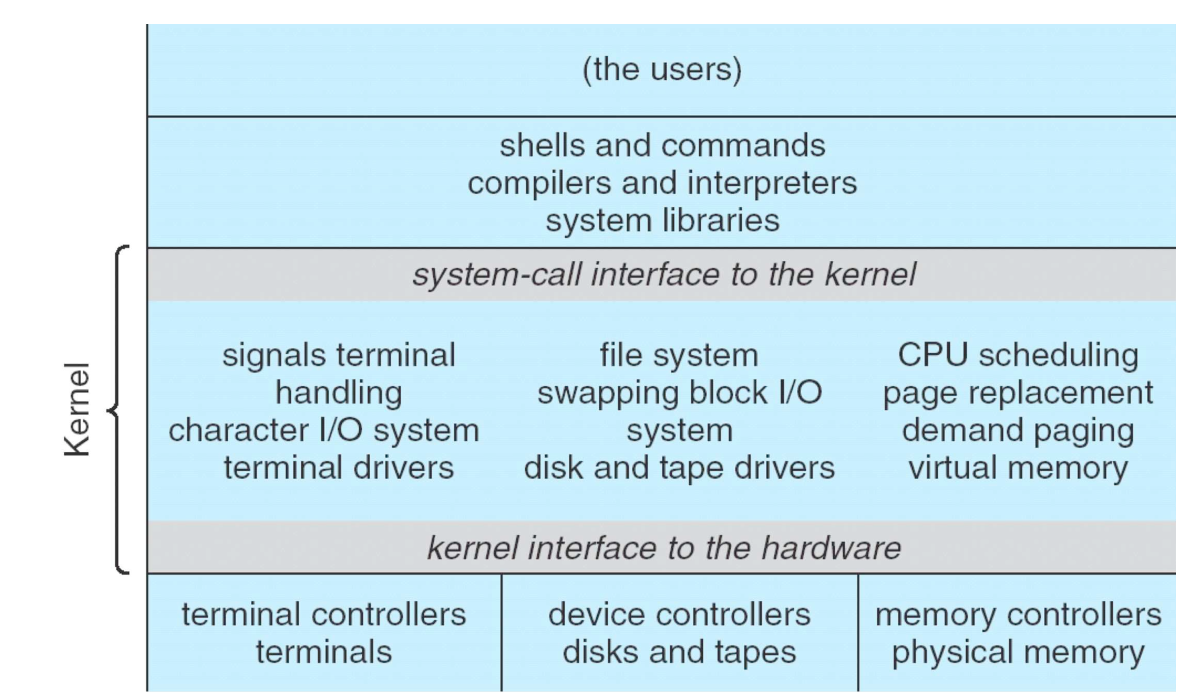

Operating Systems

Operating Systems Fundamentals

- operating system:

- provide clean, simple abstraction of hardware resources to user and applications

- manage resources: CPU, memory, display, network interfaces, …

- many processes trying to make use of shared resources

- runs in kernel mode

Good overview of OS concepts: Linux kernel labs

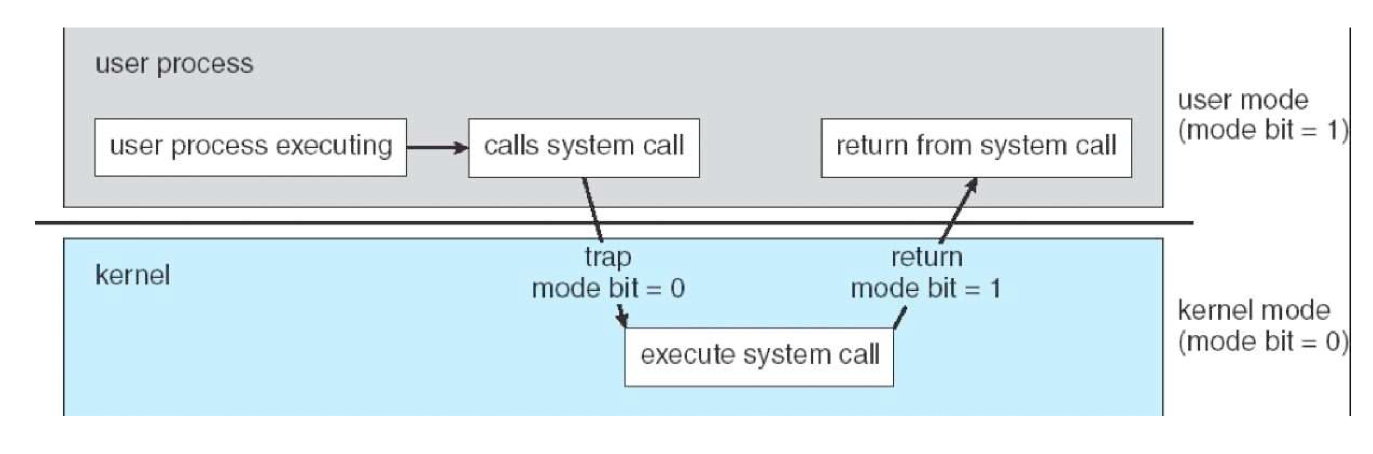

Modes of operation

- kernel: provides services as system calls to user processes e.g. read bytes from file

- not a process. Cannot be terminated

- CPUs typically have 2 modes of operation, kernel and user

- program status word: CPU register storing current mode

- kernel mode: full access to all hardware, ability to execute any instruction

- user mode: subset of machine instructions is available

- instructions affecting control of the machine or do I/O are forbidden

- code running in user mode cannot issue priviliged instructions, can only access parts of memory kernel allows

- kernel/user mode distinction is foundation needed by kernel for building security mechanisms

- instructions/memory locations whose use could interfere with other processes

are privileged

- e.g. accessing I/O devices

Processes

- program: group of instructions to perform a task; static

- process: running instance of a program; dynamic

- container that holds all information to run a program:

- code/text of program

- values of variables: in memory, in registers

- program counter: address of next instruction

- set of resources: registers, open files, alarms, related processes, …

- container that holds all information to run a program:

- cooking analogy: recipe: program; cooking: process

- most processes a user interacts with are created by user

- some OS services run in privileged mode e.g. print daemon. Gives access

to disk, ability to create network connections, …

- provide services to user-level processes

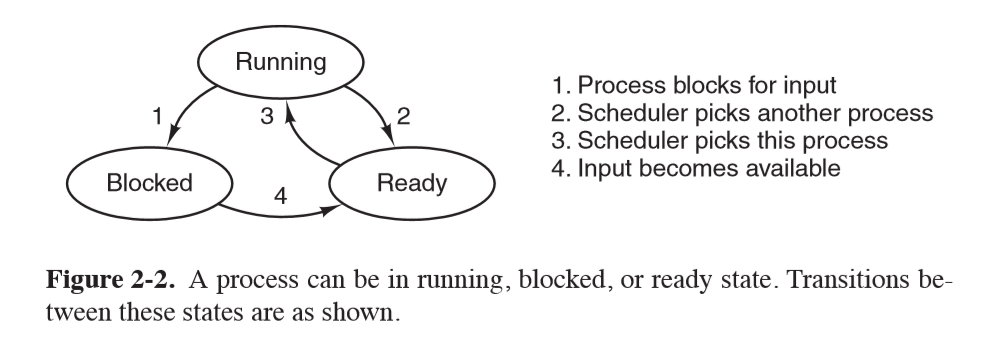

Process state

- running: using CPU

- ready: runnable; temporarily stopped while another process is running

- blocked: unable to run while waiting for external event

Process Termination

Typical conditions for process termination:

- normal exit, when a process finishes. Voluntary

- error exit, anticipated error e.g. incorrect input. Voluntary

- fatal error, unanticipated error, e.g. divide by 0. Involuntary

- killed by another process. Involuntary

- system call to verify if caller has ability to kill process

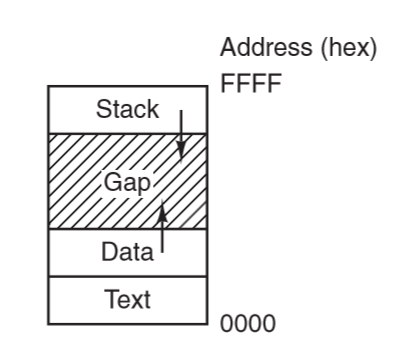

Address space

- process has its own address space: list of memory locations which the process can read/write

- text: program code, read-only

- data: constant data strings, global variables

- stack: local variables, function calls

- data segment grows upward, stack grows downward

Multiprogramming

- each process has its own virtual CPU

- multiprogramming: ability to have multiple processes share CPU by running

each for a small period of time

- increases system efficiency: maximises CPU use while waiting for I/O etc.

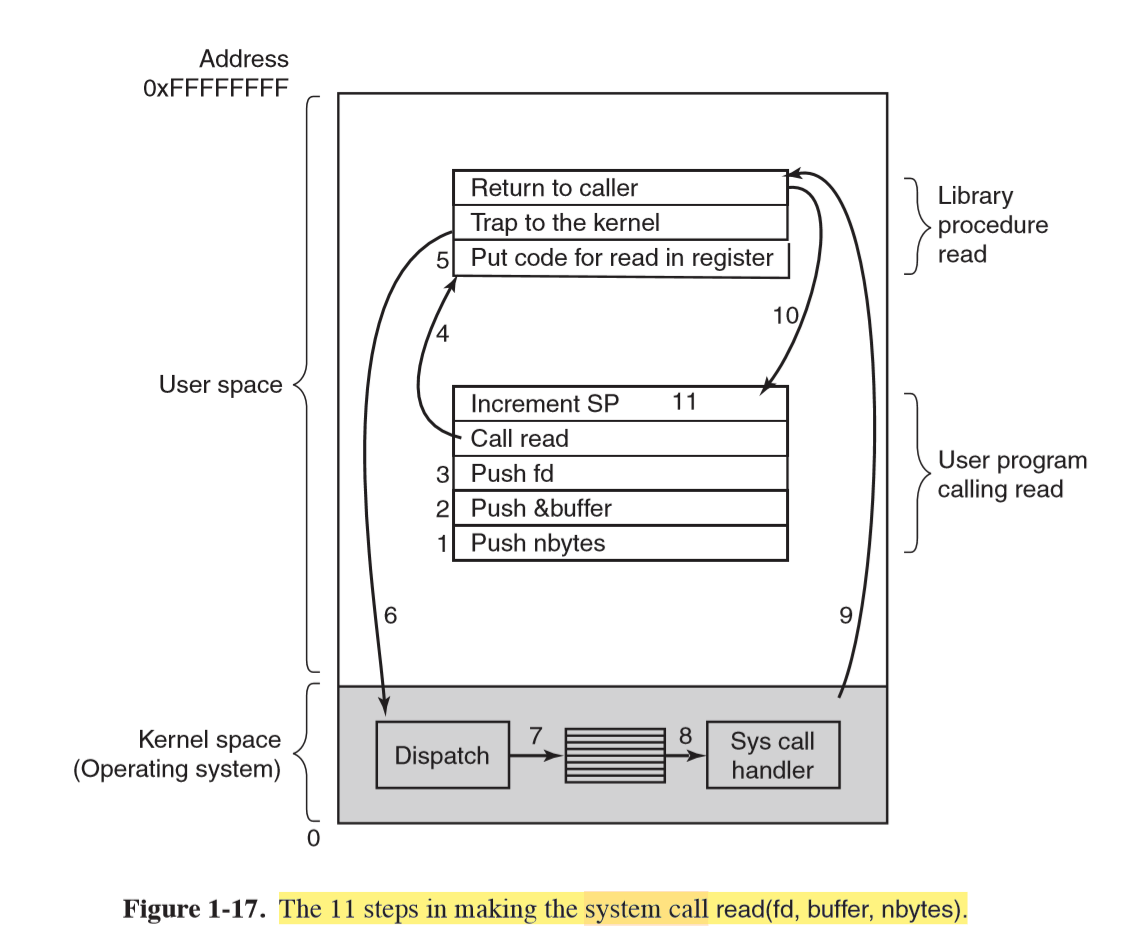

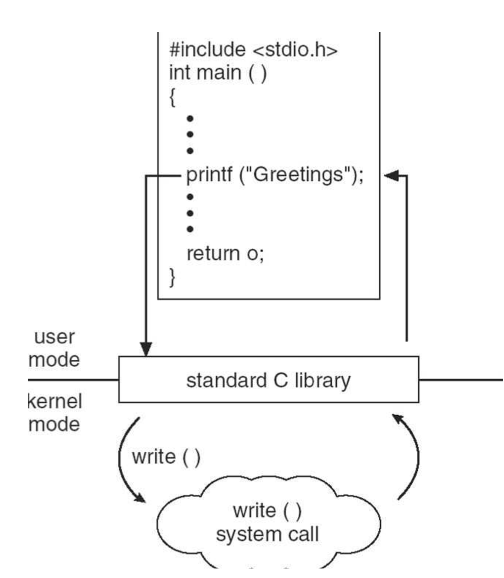

System call

- allow user programs to ask kernel to execute privileged instructions/access privileged memory

locations on their behalf

- OS checks requests before executing them to ensure integrity/security

- trap instruction: transfers control from user mode to kernel mode

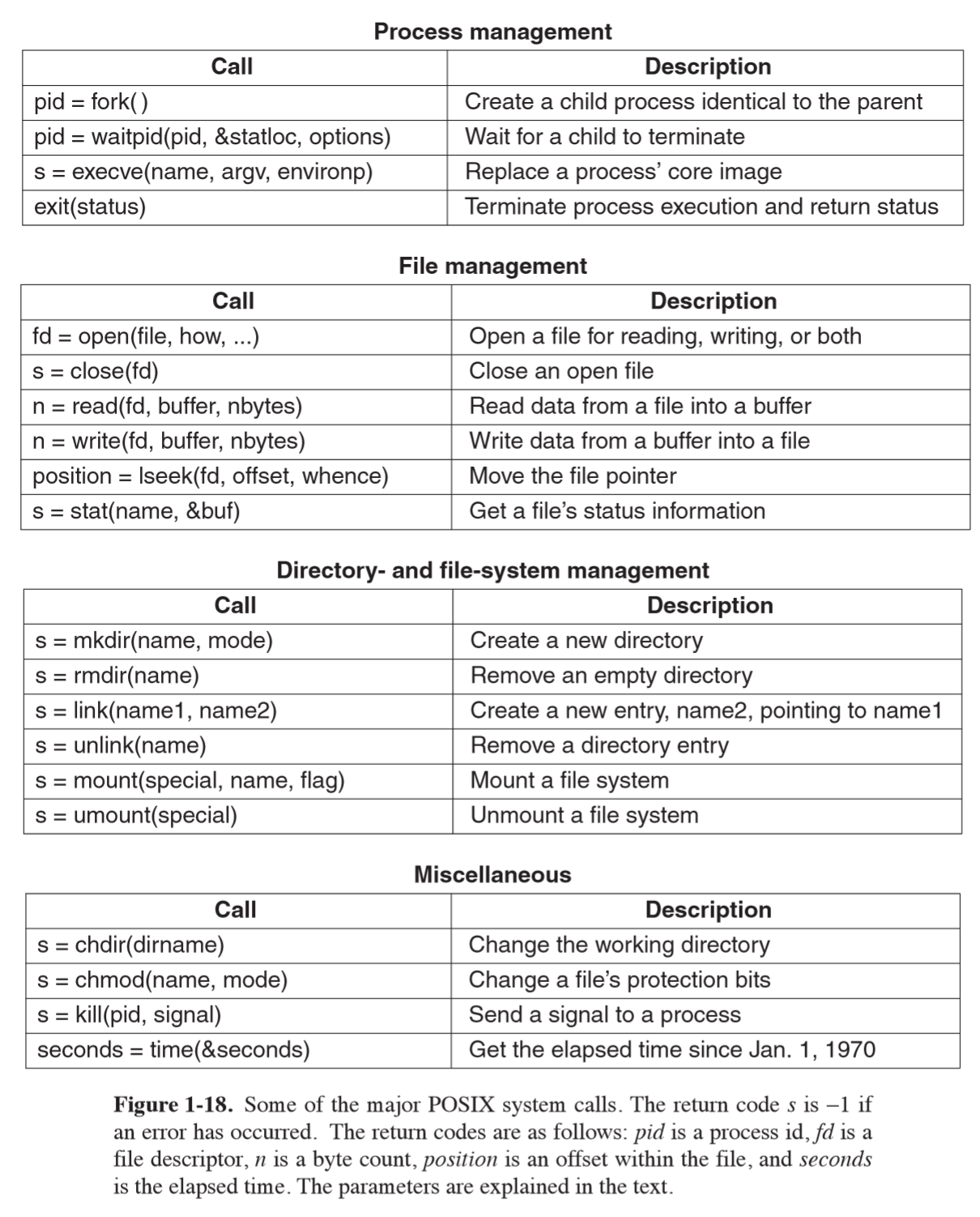

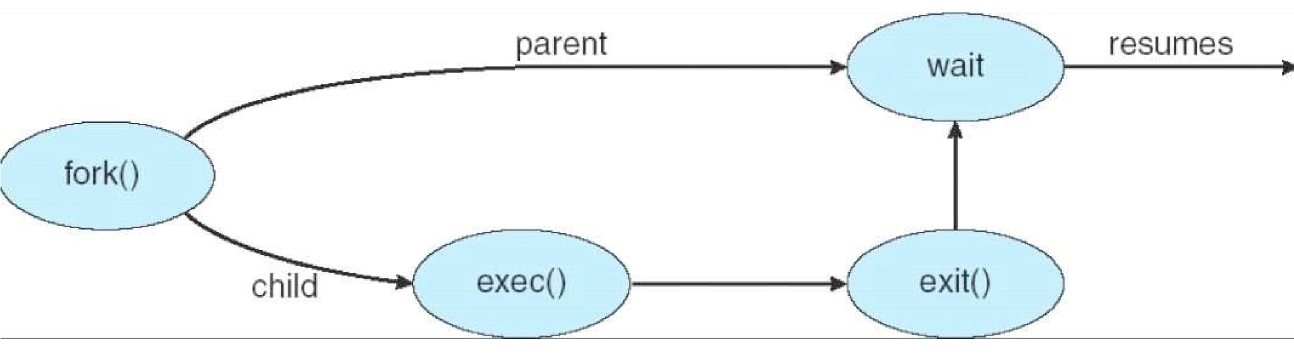

POSIX System calls

fork: creates child process that is an exact duplicate of parent process- returns 0 in child

- returns child PID to parent

- e.g. use in shell: when command is typed, shell forks off new process and must

execute the user command

- does this with

execvesystem call: replaces core image by file provided as parameter

- does this with

waitpid: wait for child process to terminateexit: terminate a process

read/write: read/write from file into a buffer

Standard C library handling of write

Interrupt

- signal to interrupt CPU that is issued when a hardware device needs CPU attention

- e.g. it has finished carrying out current command and is ready for the next one

- asynchronous with currently executing process

- CPU hardware takes values in program counter and PSW registers and saves them in privileged memory locations reserved for this purpose

- replaces them with new values, and move to kernel mode

- replacement program code causes execution to resume at start of the interrupt handler, code that is part of kernel

- interrupt vector: address of interrupt handler. Functions:

- save rest of status of current process

- service the interrupt

- restore what was saved

- execute a return from interrupt to restore previous state

- pseudo-interrupt: from CPU itself, c.f true interrupts from devices external to CPU

- exception: user program generates pseudo-interrupt inadvertently e.g. divide by 0

- may cause process termination

- can also be created intentionally by user mode executing special instruction e.g. TRAP

- exception: user program generates pseudo-interrupt inadvertently e.g. divide by 0

Process table

- one entry per process

- contains state info to resume a process

- process management: registers, program counter, PSW

- memory management

- file management

Threads

- thread: sequential execution stream within a process

- basic unit of CPU utilisation

- threads are a lightweight process:

- faster to create and destroy than processes

- useful when number of threads needs to change rapidly/dynamically

- no performance gain when all are CPU bound, but performance gain when substantial I/O

- main motivation: handle multiple activities at once, where any one activity may block. Introducing threads allows multiple sequential threads to run quasi-parallel, simplifying programming model

- example: web server

- dispatcher thread reads incoming requests

- passes work to an idle worker thread that performs a

read - when the worker blocks on disk, another thread is chosen to run

- without threads the CPU would be idle every time disk IO was occurring

- example: heavy data processing

- process blocks while data IO in progress

- input thread, output thread, processing thread:

- input thread writes to input buffer

- processing thread reads from input buffer and writes to output buffer

- output thread reads from output buffer and writes back to disk

- example: text editor: consider replacing one word through entire large file

- single thread: long time to process: user will be blocked from other actions until this is complete

- multiple threads: 1 thread edits currently displayed contents, spawn 2nd thread

to make replacements through the rest of the document (in the background)

- separate process: bad solution as they are editing the same file

- 3rd thread may be used to save to disk

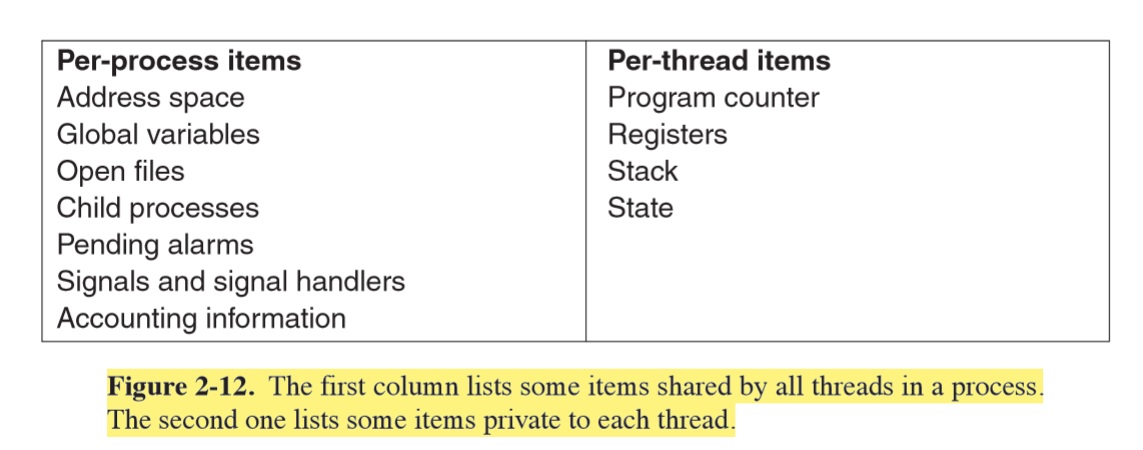

Classical thread model

- c.f. Linux thread model, which blurs line between process and thread

- process: way of grouping related resources for simple management. It has:

- address space (program text + data)

- other resources (open files, child processes, …)

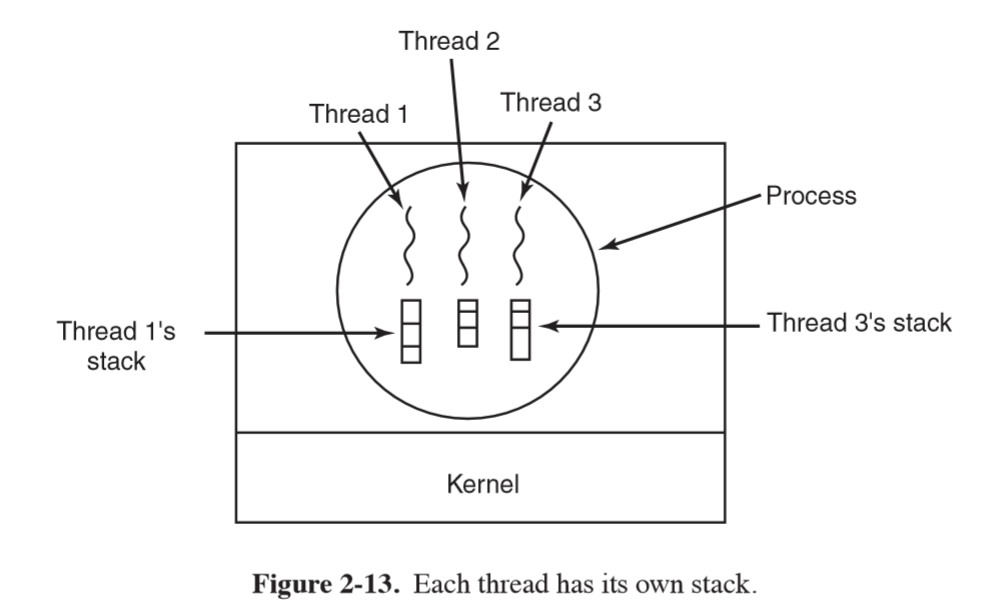

- thread of execution/thread: executes in some process. It has:

- program counter

- registers

- stack

- processes group resources; threads are entities scheduled for execution on CPU

- threads allow multiple executions to occur in same process environment, to a degree independently

- multiple threads have reduced overhead c.f. multiple processes

- less time to create new thread

- less time to terminate

- less time to switch between threads (no system call needed)

- less time to communicate between threads (no system call needed)

- every thread can access every memory address in process address space

- one thread can read/write/wipe out another thread’s stack

- no protection between threads: not possible and shouldn’t be necessary, as process is always owned by a single user that should be aware of threads created

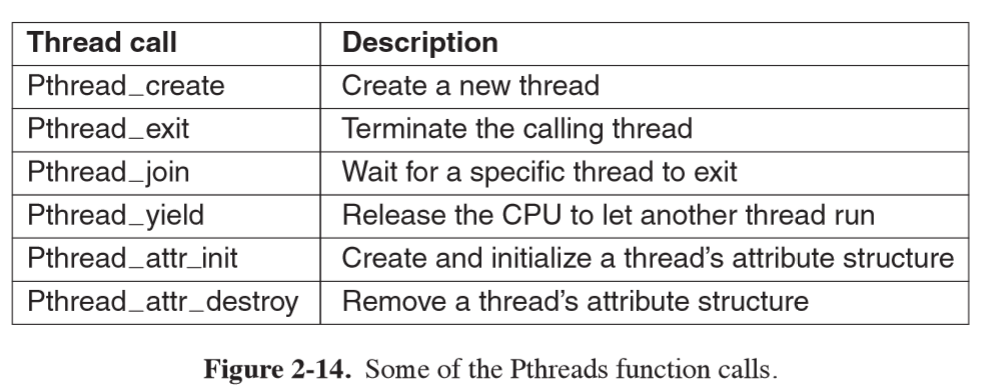

POSIX Threads pthreads

- each pthread has:

- id

- set of registers + program counter

- set of attributes: stack size, scheduling parameters, …

pthread_create: returns thread identifier- similar to

fork

- similar to

- global variables shared

- thread switches can occur at any point: synchronisation important! e.g. so you don’t overwrite value in memory used by another thread

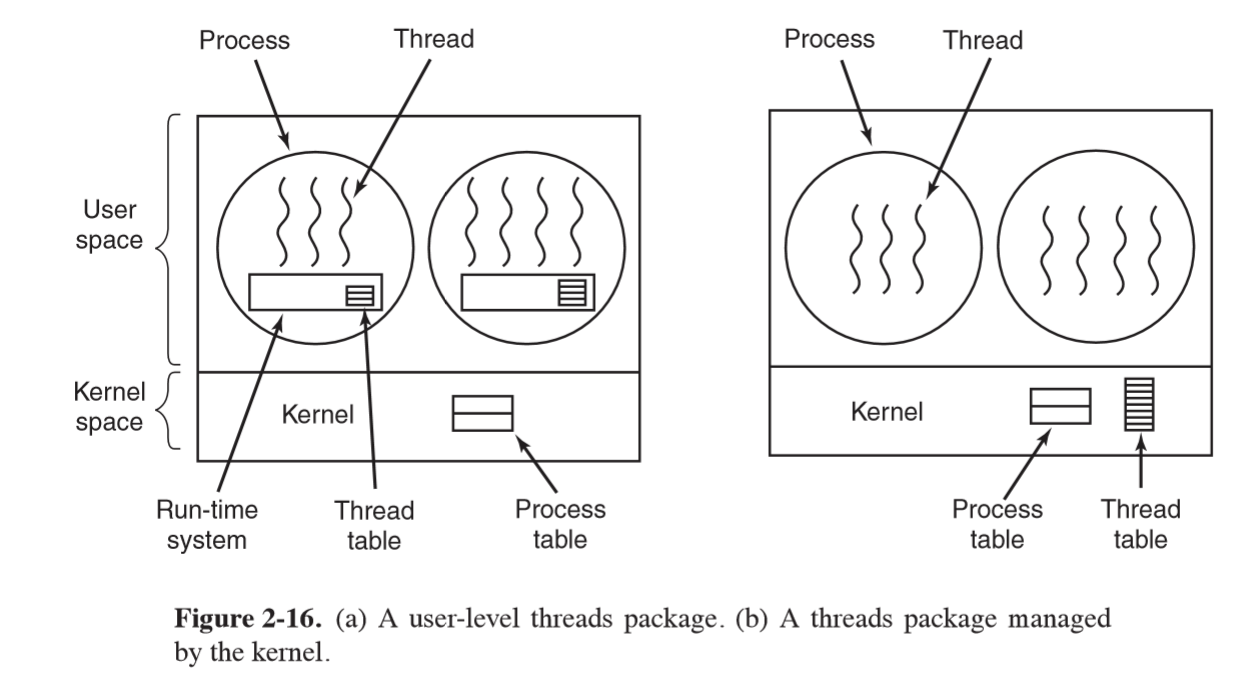

User-level threads vs kernel-level threads

- user-space:

- implemented by library

- kernel unaware of threads

- each process needs to maintain private thread table

- advantage:

- thread switching much faster as no system call needed

- OS doesn’t need to support threads

- can customise scheduling

- scales well for large number of threads as you aren’t taking up table/stack space in kernel

- disadvantage:

- blocking system calls: if a thread makes the call this will stop all threads

- requires mechanism to tell in advance if calls will block

- threads causing page faults will also cause kernel to block the process even thought other threads may be able to run

- if thread starts running, no other thread will ever run unless first thread voluntarily yields. There are no clock interrupts in the process

- kernel space

- kernel maintains thread table

- threads created/destroyed etc through system calls

- advantage:

- kernel is aware of threads, so when one thread blocks it may schedule another thread of the same process to run

- doesn’t require additional non-blocking system calls

- disadvantages:

- cost of a system call is substantial: if thread creation/removal etc is common will have much higher overhead

- needs to be implemented in OS

Process Communication

Interprocess Communication

- increase efficiency through cooperation

- exchange information between processes

- concerns:

- processes could interfere with each other

- sequencing, order

- ensure system integrity

- predictable behaviour

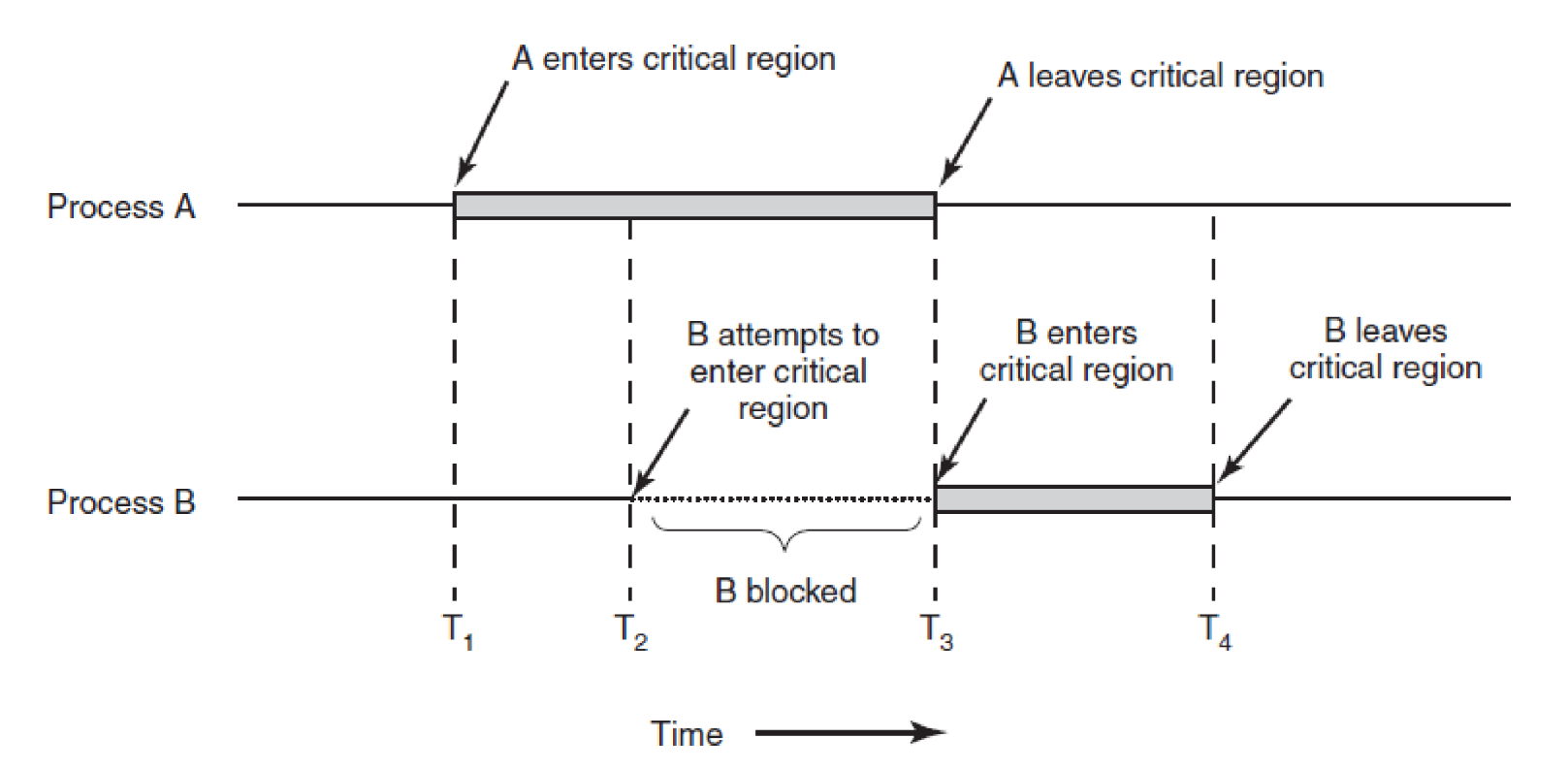

Race Conditions

- multiple processes have access to a shared object (e.g. a file), to which they

can all read/write

- race condition: output depends on the order of operations

- hard to debug: non-deterministic; cannot predict in advance how scheduler will determine order

- e.g. 2 processes attempting to add their job to print queue

- critical region: section of code in which mutual exclusion is required

- prohibit access to shared object at the same time

Requirements for solution to avoid race conditions

- no two processes may simultaneously be inside critical regions

- no assumptions about speeds/number of CPUs

- no process outside critical region should block other processes

- no process should have to wait forever to enter critical region

Avoiding race conditions

Methods for avoiding race conditions include:

- disabling interrupts: not a good option as requires giving lots of power to user process

- strict alternation

- test and set lock

- sleep and wake-up

- semaphores, monitors, message passing

Strict alternation with busy waiting

// process A

while (TRUE) {

while (turn != 0) { }

critical_region();

turn = 1;

noncritical_region();

}

// process B

while (TRUE) {

while (turn != 1) { }

critical_region();

turn = 0;

noncritical_region();

}

turnflag indicates whether it is process A/B’s turn- issue: if process B is much slower than A in non-critical region it will end up being blocked by B

- doesn’t meet requirements: blocked by a process not in critical region

Test and Set Lock (TSL)

- test and set lock CPU instruction:

TSL RX, LOCK

- atomic operation:

- reads contents of variable

LOCKinto regiserRX - stores nonzero value at

LOCK

- reads contents of variable

- no other processor can access the memory word until the instruction is finished: the CPU locks the memory bus to achieve this

- assume when

LOCKis 0, any process may set it to 1 usingTSLinstruction, then read/write shared memory. When done it setsLOCKback to 0 using ordinaryMOVE

Entering and leaving critical region using TSL instruction

enter_region:

TSL REGISTER,LOCK // copy lock to register, set lock to 1

CMP REGISTER,#0 // was lock 0?

JNE enter_region // if not, lock was set, so loop

RET // return to caller; critical region entered

leave_region:

MOVE_LOCK,#0 // store 0 in lock

RET // return to caller

Busy Waiting

- busy waiting: check if allowed to enter critical region. If not, execute loop until allowed

- wastes CPU

- priority inversion:

- low priority process may starve: low priority process L is in critical region. High priority process H becomes ready. H begins busy waiting, but L is never scheduled while H is running, so L never gets to leave critical region, and H loops forever

Blocking

- approach:

- attempt to enter critical region

- if available, enter

- otherwise: register interest and block

- when critical section available, OS unblocks process waiting for critical region

sleep: system call that causes caller to block (suspend) until another process wakes upwakeup: system call that wakes a process- improves CPU utilisation over busy waiting

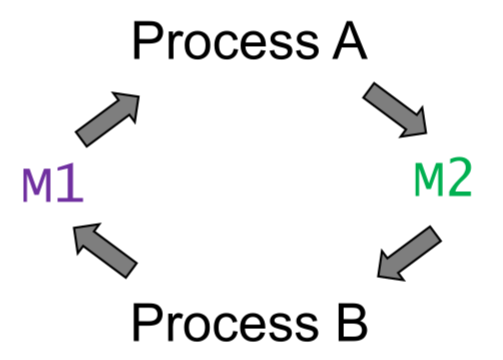

Deadlock

- deadlock: multiple processes in set are waiting for an event that only another process in the set can cause

- approaches:

- detection and recovery

- careful resource allocation: typically impractical as you cannot know ordering of accesses

- prevention: prohibit process to have > 1 lock at a time

- detection: model processes/locks as graph. existence of cycle implies deadlock

Process Scheduling

Process Scheduler

- process scheduler: determines which process to run, and for how long based on

its scheduling algorithm

- input: processes in ready state (kept in run queue)

- scheduling varies for different workloads and environments

- e.g. email: idle most of the time

- e.g. rendering video requires lots of CPU

- e.g. does user need real-time feedback

- scheduler has limited information about processes

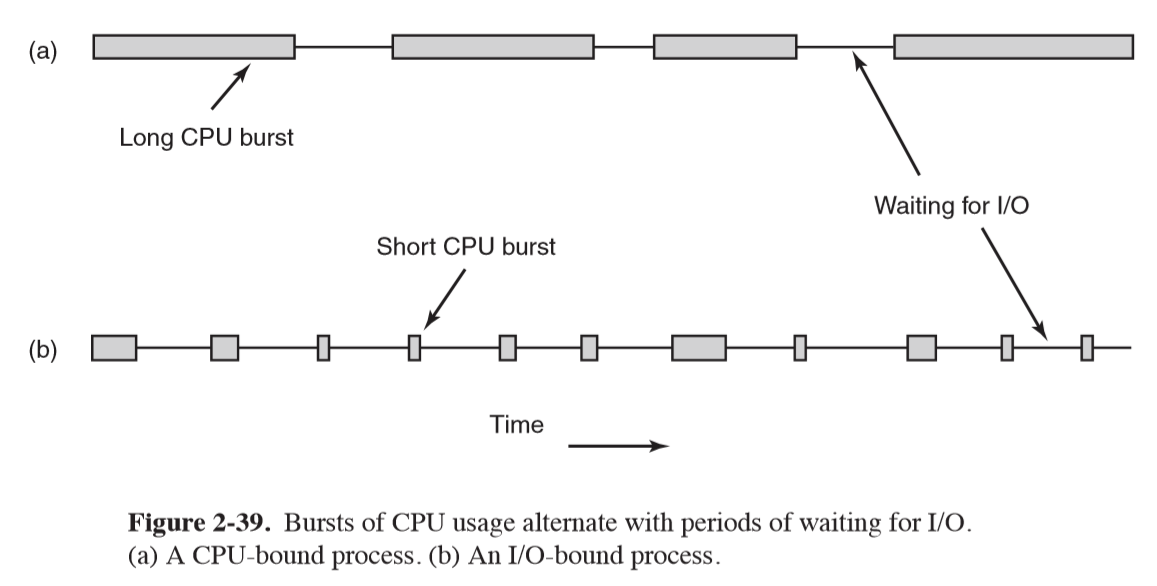

Processes can be categorised as being CPU-bound or I/O-bound:

- CPU-bound: long periods of processing, and infrequent I/O waits

- I/O-bound: short bursts of processing, and frequent I/O waits

- determined by length of CPU burst, not length of I/O burst

- as CPUs get faster, processes tend become more I/O-bound

Scheduling decisions are made:

- when a new process created

- when a process exits

- when a process blocks (for I/O etc.)

- when an I/O interrupt occurs

Scheduling Algorithms

- non-pre-emptive scheduling algorithm: picks a process to run and lets it run until it blocks or voluntarily yields CPU

- pre-emptive scheduling algorithm: picks a process and lets it run for maximum fixed time

- process is then suspended

- clock interrupt used to signal process has used up time interval

-

algorithm chosen depends on environment:

- batch: periodic analytic tasks, e.g. bank transaction consolidation, high performance computing jobs

- Nonpreemptive, or preemptive with long quantum often acceptable

- reduce process switches, improves performance

- interactive: user facing, servers

- need to prevent one process hogging CPU and denying service to others

- preemption needed

- real-time: need answer at certain time e.g. air traffic control

- processes know they may not run for long period of time, so they do their work and block quickly

- preemption sometimes not needed

- only runs tasks specific to purpose at hand, c.f. interactive systems which are general purpose

- context switch: (aka process switch) involves saving and reloading process state

- saving, loading registers and memory maps

- update various memory tables, lists

- takes time

Scheduling Algorithm Goals

All systems

- fairness: give each process fair share of CPU

- policy enforcement: e.g. policy where safety control process can run whenever it needs to, even though this may make payroll process 30s late

- balance: keeping all parts of system busy

Batch Systems

- throughput: maximise jobs complete per unit time

- turnaround time: minimise time between submission and termination

- CPU utilisation: keep CPU busy all the time

Interactive

- response time: respond to requests quickly: prioritise interactive requests

- proportionality: meet users’ expectations i.e. how long a user things an action should take

Real-time

- meeting deadlines: e.g. process reading data from data-collection device needs to avoid losing data

- predictability: e.g. multimedia systems, audio jitter

Scheduling Algorithms

First-come first served

- batch systems

- processes are assigned CPU in order they request it

- maintain queue of ready processes

- if current process is blocked CPU is handed to next process in queue

- when blocked process becomes ready it is enqueued

- pro: simple, fair

- con: CPU bound process competing with many I/O bound processes. Will take very long time for it to receive CPU time

Shortest Job First

- batch systems

- assumption: run times are known in advance

- e.g. running batch of 1000 claims will take similar time every day

- scheduler picks shortest job to run first: minimises turnaround time

- not optimal if processes don’t arrive at the same time

Round-Robin Scheduling

- interactive systems

- simple, fair

- each process is assigned a quantum (time interval) during which it is allowed to run

- if it is still running at the end of the quantum, CPU is preempted and given to another process

- choosing quantum length:

- too short: lots of overhead on process switching, poor CPU utilisation

- too long: poor response to interactive requests

- 20-50ms usually good compromise

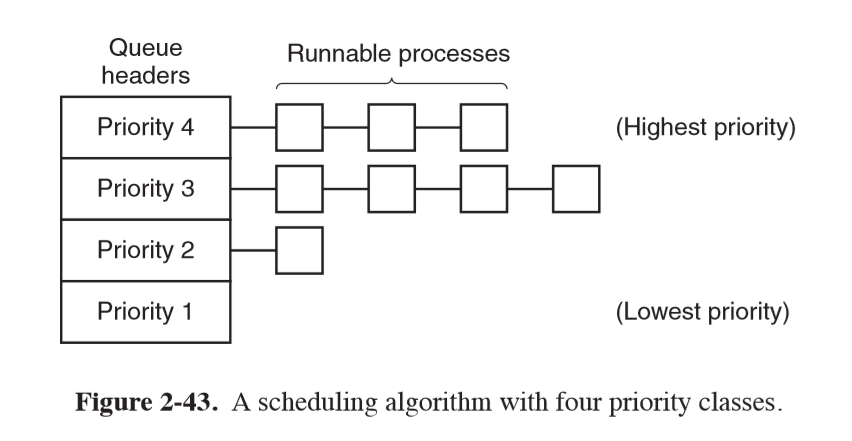

Priority Scheduling

- interactive systems

- each process is assigned a priority, and runnable process with highest priority is allowed to run

- system processes usually more important than user processes

- scheduler may decrease priority of running process at each clock interrupt to prevent process running indefinitely

- when priority drops below that of another process, context switch occurs

- alternate approach: maximum time quantum

- priority can be allocated:

- statically: e.g. every process created by user X has priority Y

- dynamically: system allocates priority based on achieving system goals

- e.g. I/O bound process should be given high priority when it is ready, as it will spend long time occupying memory and can shoot off next I/O request

- e.g. give priority $1/f$, f: fraction of last quantum a process used

- another approach: group processes into priority classes and use priority scheduling between classes,

use round robin within classes

- e.g. as long as there are processes in priority 4, run them in round robin. Then run priority 3 processes in round-robin, etc.

- starvation: priority needs to be adjusted regularly to ensure that low priority processes receive CPU time if higher priority jobs constantly arrive

Others

- shortest process next

- guaranteed: every process guaranteed some portion of CPU time

- lottery: randomised with priority bias

- fair-share scheduling: each user given portion of CPU time

Memory Management

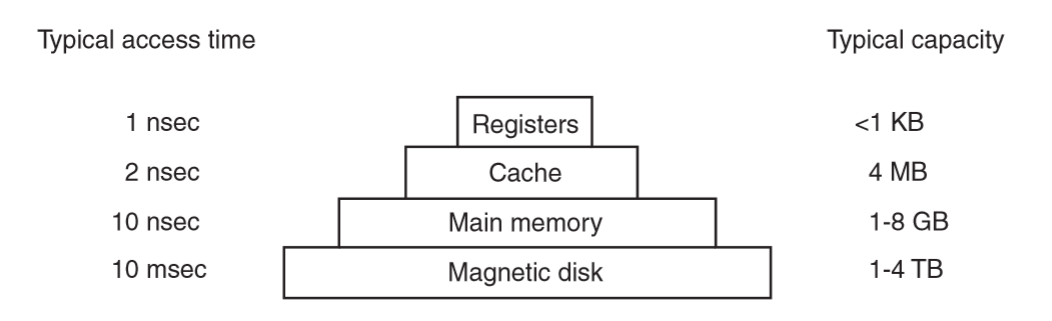

Memory hierarchy

Ideally:

- fast

- cheap

- large

- non-volatile

Reality:

- different memory types with different properties

- higher speed, smaller capacity, greater cost

- cost increases up the pyramid

- distance from CPU decreases up the pyramid

- size decreases up the pyramid

- registers: internal to CPU, as fast as CPU, no delay in accessing

- programs decide what to keep in them

- cache: managed by hardware

- fast random access

- L1 cache, on CPU, very fast

- other caches may be shared between cores

- store frequently accessed data

- cache hit: cache line is in the cache, no memory request sent to main memory

- cache miss: need to go to memory with substantial size penalty

Memory allocation and management

- memory manager: part of operating system managing part of memory hierarchy

- to keep track of which parts are in use

- allocate/deallocate memory to processes as needed

- protect memory against unathorised accesses

- simulate appearance of bigger main memory by moving data automatically between main memory and disk

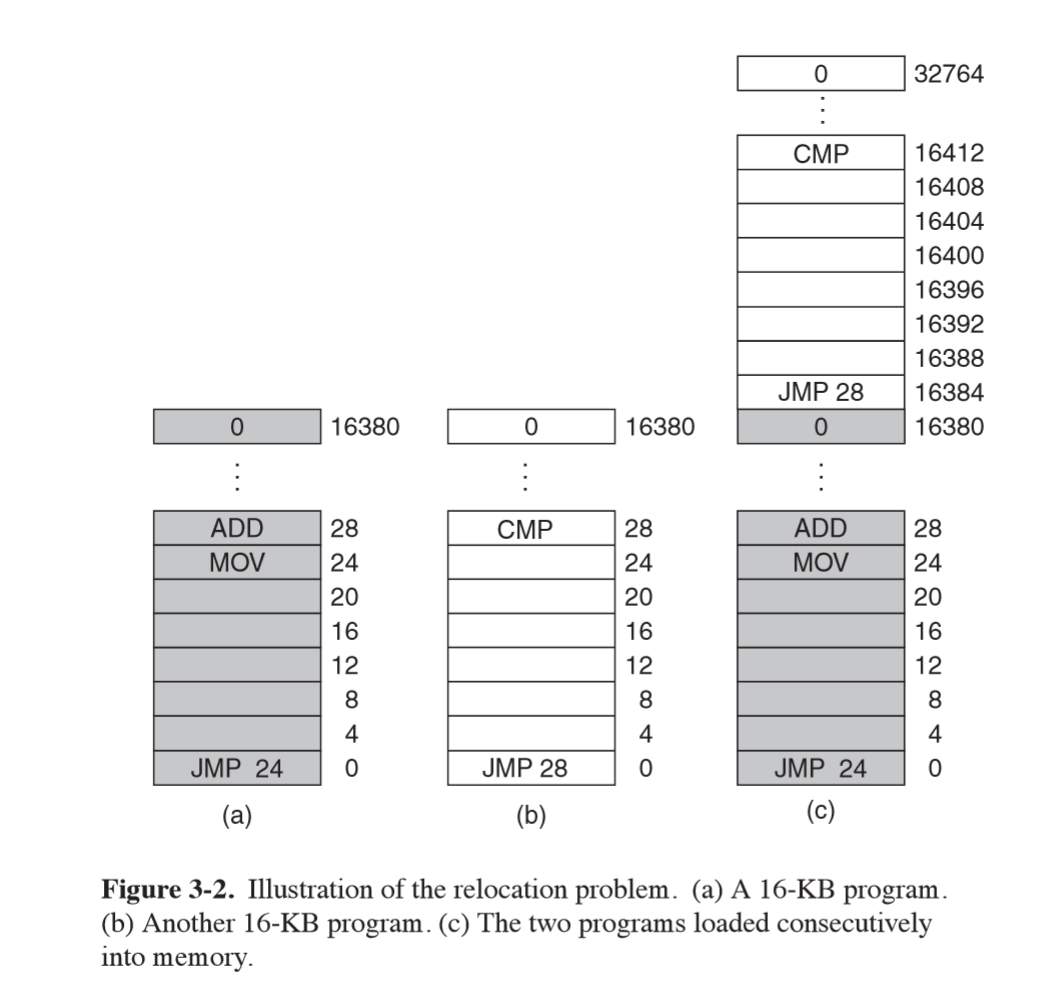

No Memory Abstraction

- expose absolute physical memory to processes

- issues: security, multiple processes

- prevention of processes from overwriting what they shouldn’t

- relocation problem: multiple processes loaded into memory, sequentially

JMP 28in process (b) results in access of address of process (a) , likely causing it to crash- both processes reference absolute physical memory

- still common in embedded systems

Memory Abstraction: Address spaces

- exposing physical memory:

- difficult to have multiple programs running at once

- easy for user programs to trash operating system

- address space: abstraction; set of addresses a process can use to address memory

- each process has its own address space, independent of those belonging to other processes

Simple dynamic relocation approach that used to be common, hardware support with base and limit registers:

- base register: loaded with physical address where program begins in memory

- limit register: loaded with length of program

- every time a process references memory CPU hardware automatically adds base value to address generated by the process before sending address to memory bus

- disadvantage: needs extra addition and comparison on every memory reference

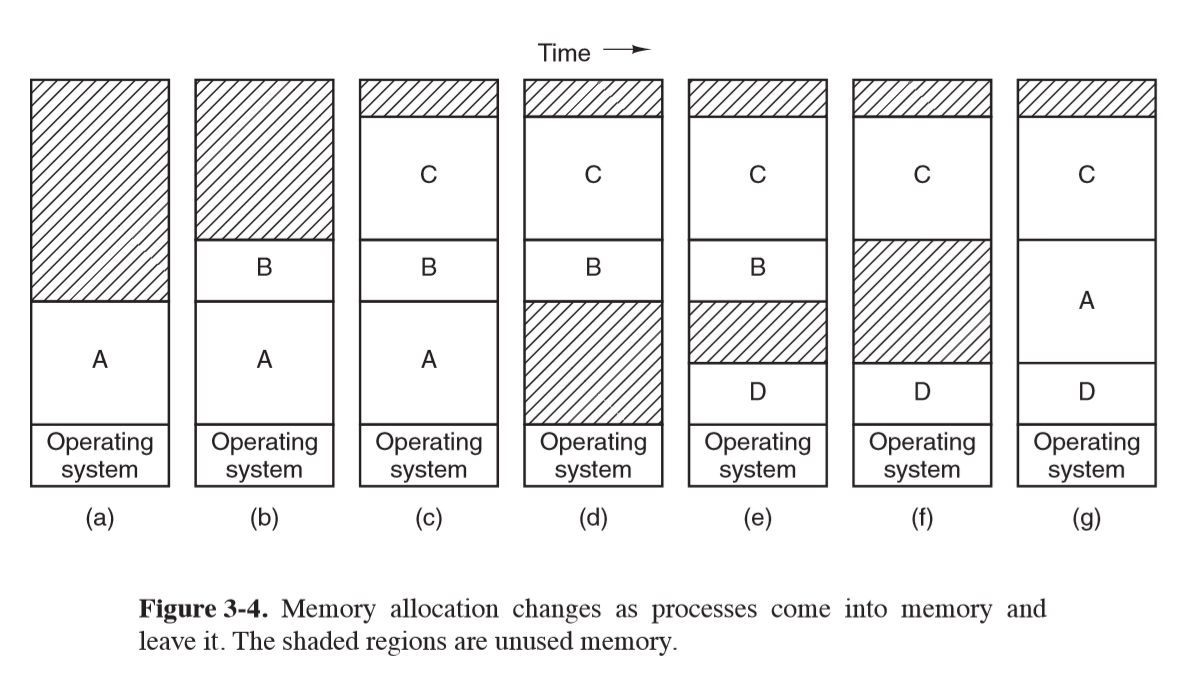

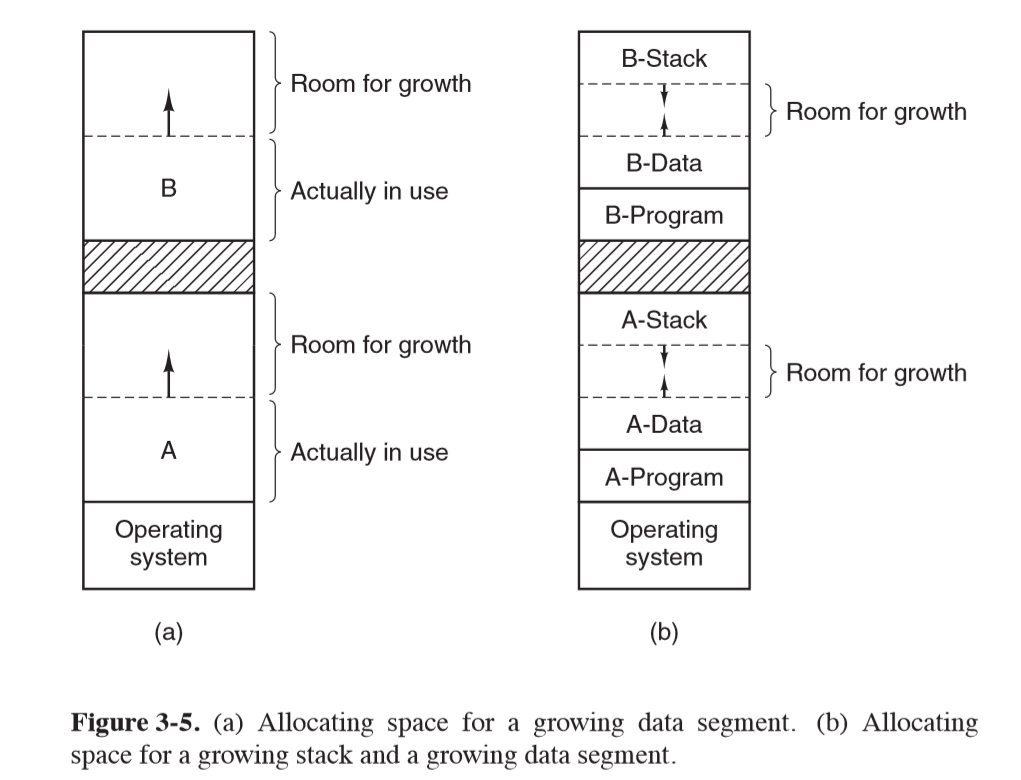

Swapping

- assume physical memory is large enough to hold a given process

- swapping: load each process in entirety, run for a while, then put back on disk

- idle processes mostly stored on disk so they don’t take up memory when not running

- if insufficient room for process to grow in memory and swap area is full, process needs to be suspended until space is freed

- if expected that most processes will grow, good idea to allocate extra memory when a process is swapped in or moved to reduce overhead

Managing free memory

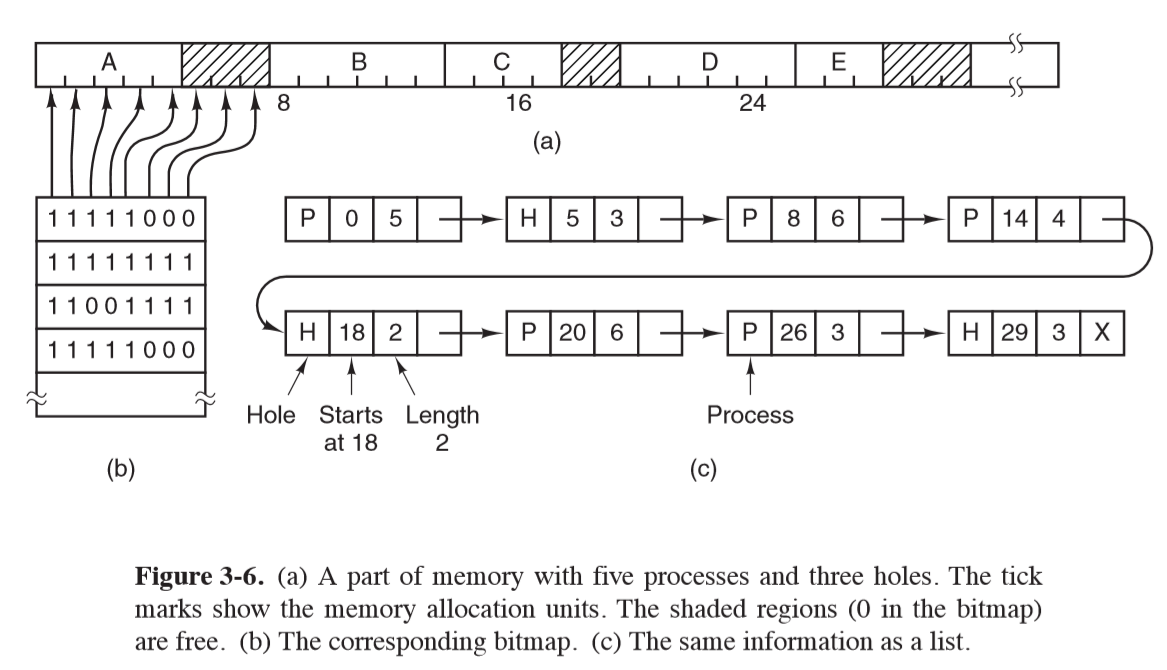

Bitmaps

- memory is divided into allocation units, which corresponds to a bit in the bitmap

- 0 = free, 1 = occupied

- issue: when you decide to bring k-unit process into memory, memory manager must search bitmap to find run of k consecutive bits in the map: slow $\Theta(n)$

Linked Lists

- maintain double linked list of allocated/free memory segments

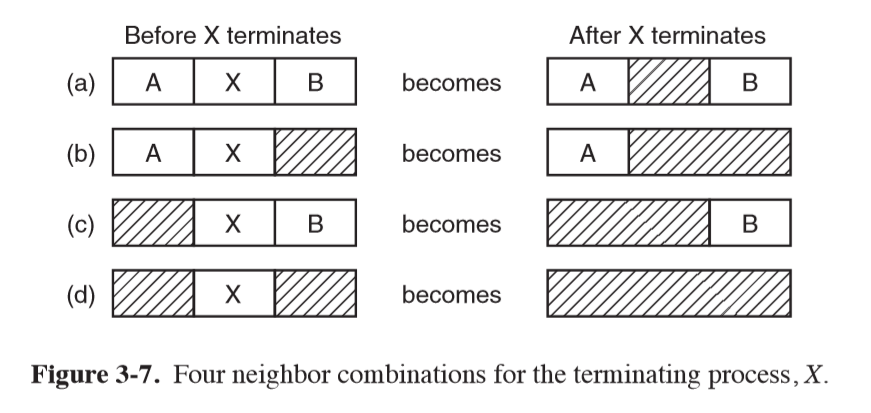

- each segment contains either a process or a hole

- terminating process requires replacing process with hole, may require entries to merge

- stored sorted by memory address: easy to find a block to fill

Memory Allocation Algorithms

- first fit: put new process in first hole of sufficient size

- next fit: keeps track of where it is whenever it finds a suitable hole, starts

searching from here next time

- slightly worse performance than first fit

- best fit: widely used. Searches entire list and take smallest adequate hole

- slower than first fit, as searches entire list

- more memory wasted than first fit/next fit because it leaves small useless holes

- worst fit: take largest available hole; not a good idea either

- all of these can be sped up by maintaining separate lists for processes and holes

- speed up for allocation; slowdown for deallocation

- quick fit: maintain separate list for common sizes requested

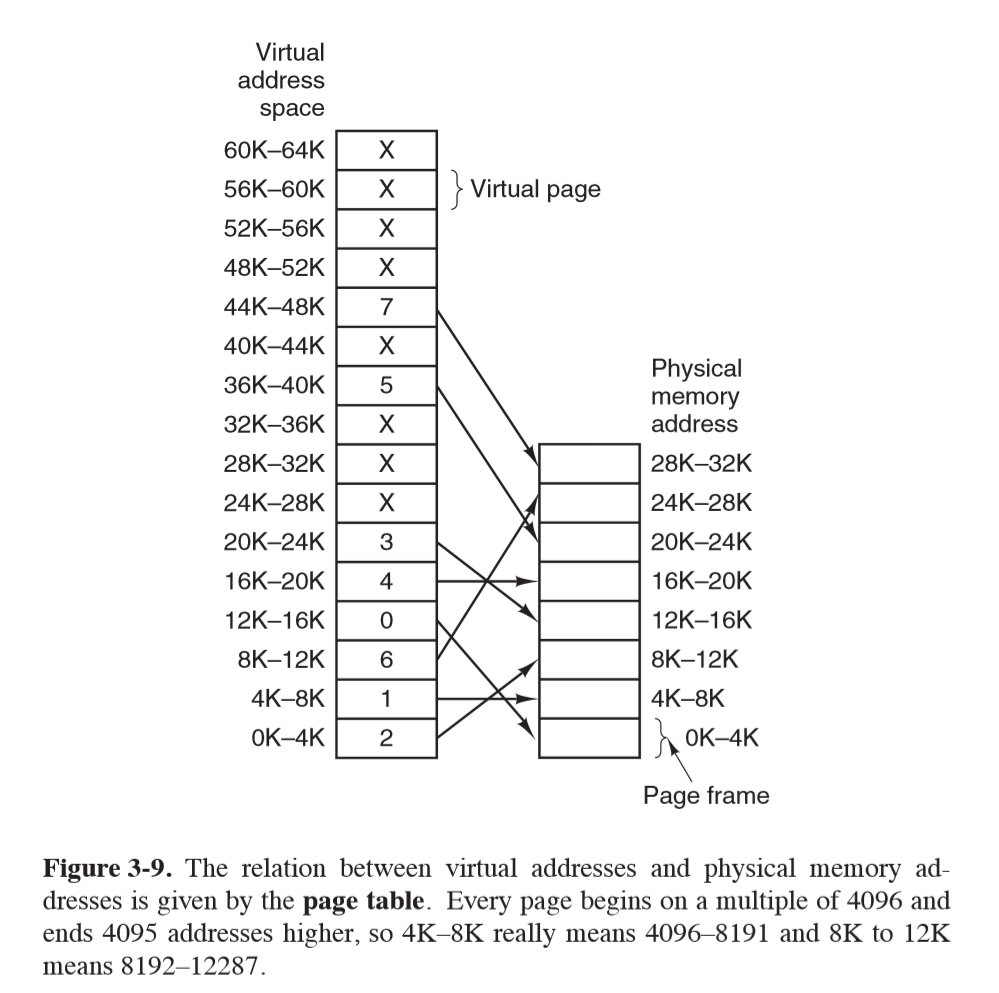

Virtual memory

- overlays: approach in 1960s, splitting programs into pieces called overlays

- when program was started, only the overlay manager was loaded, which immediately loaded/ran overlay 0. Subsequent overlays were either placed above overlay 0 if space was available or on top of overlay 0 if no space was available

- responsibility of developer to break software into overlays: repetitive, boring error prone work

- extra complexity, replicated for every program

- virtual memory: used when need to run a process that cannot fit in memory

- support multiple programs running simultaneously, each of which fits in memory but collectively exceed memory: swapping has large I/O costs

- allows programs to run when only partially loaded in memory

- each process has address space broken up into pages, a contiguous range of addresses

- from point of view of process it looks like it has contiguous memory

- virtual address space may be larger than physical address space

- pages are mapped onto physical memory, but not all pages need be in physical memory at the same time to run the program

- pages typically 4kB

Fragmentation

- external fragmentation: unused memory external to/between pages

- internal fragmentation: unused memory internal to pages, where page size

- paging wastes a fraction of a page for each process as process memory needs unlikely to be exact multiple of page size

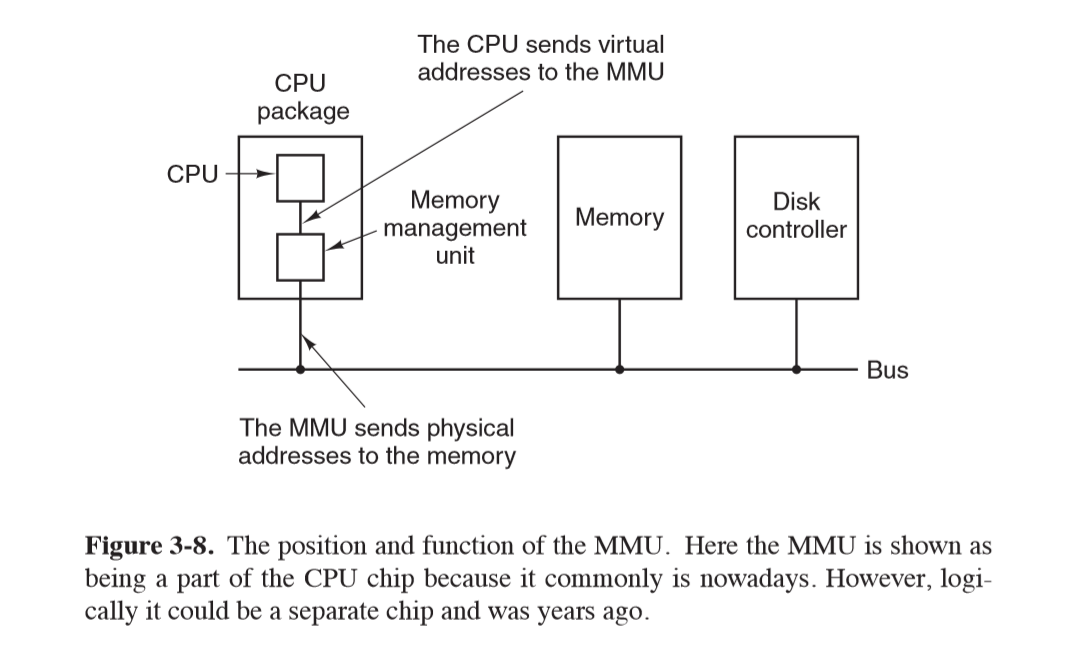

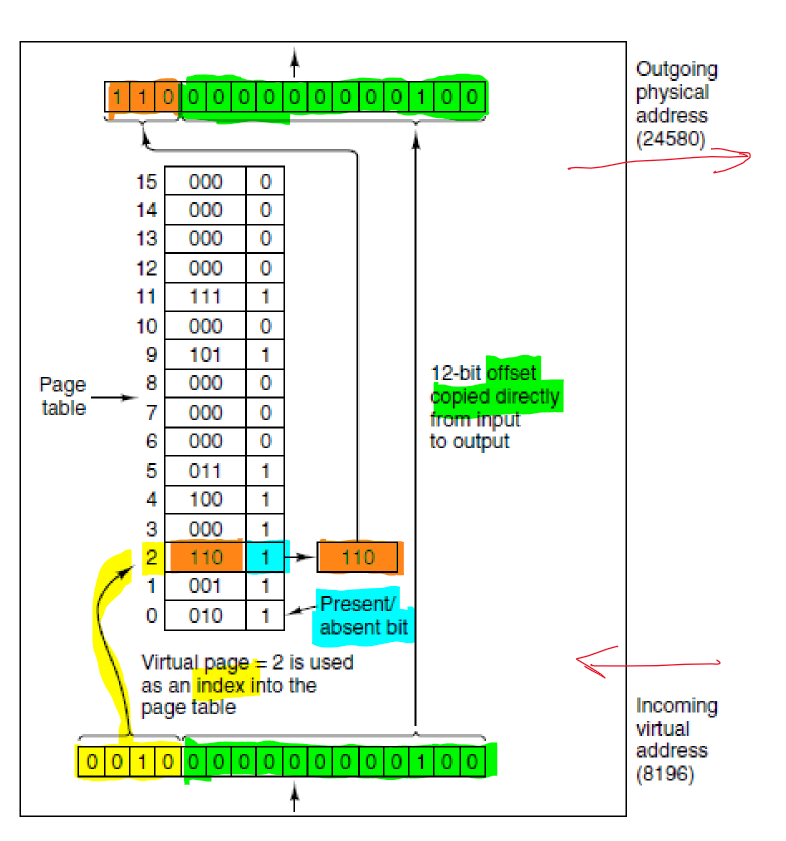

Memory management unit MMU

- memory management unit: maps virtual addresses to physical memory addresses

- page frame: page in physical memory

- page table: stores mapping of virtual pages to page frames

- present/absent bit: indicates if page is physically present in memory

- page fault: occurs when virtual page is not physically present in memory

- CPU traps to OS, which evicts a page frame if necessary and writes contents to disk

- fetches from disk the referenced page, updates the page table, and restarts trapped instruction

- virtual address

- high order bits: virtual page number, indexing page table for the page frame number

- offset: low order bits

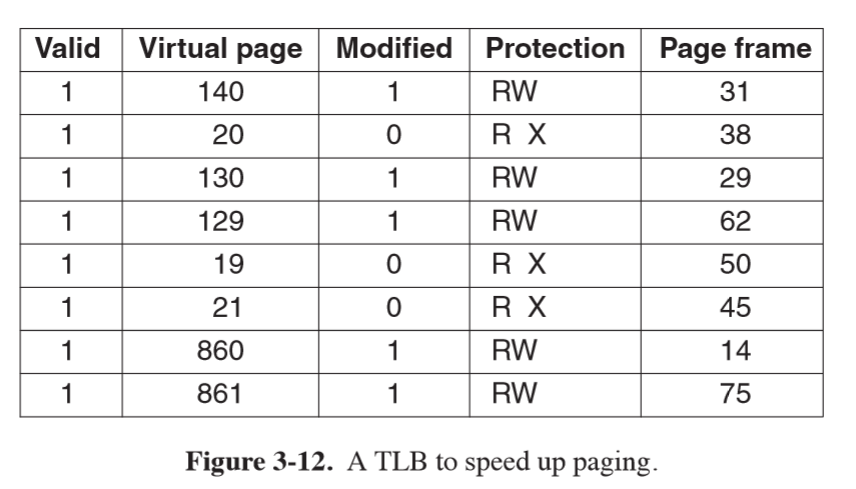

Page Table Entry

- page frame number: mapping between virtual page number and page frame number

- protection: permitted access: e.g. 3 bits for read/write/execute

- present/absent:

- 1: valid entry and used.

- 0: virtual page currently not in memory, causes page fault

- modified: dirty/clean.

- dirty: if page has been modified it will need to be written back to disk

- clean: if page hasn’t been modified it can be dscarded

- referenced: set whenever page is referenced, useful for eviction

- pages not being used are better eviction candidates

- caching disabled: important for pages mapping onto device registers instead of memory

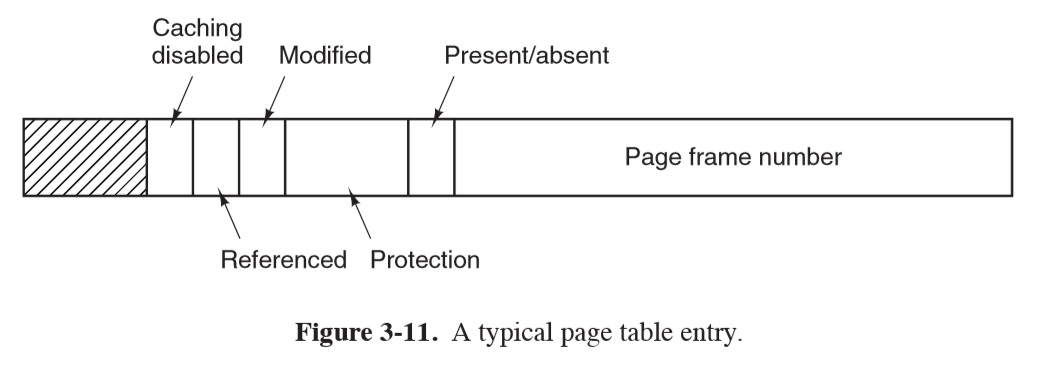

Translation lookaside buffer

- issues with paging:

- mapping needs to be fast: must be done for every memory reference

- could have array of hardware registers: unbelievably expensive

- alternatively could have page table entirely in memory: very slow

- if virtual address space is large, page table will be large

- mapping needs to be fast: must be done for every memory reference

- most programs tend to make large number of references to small number of pages

- only small fraction of page table entries are heavily read, while the rest are barely used

- translation lookaside buffer: speeds up page access by acting as cache for recently accessed

page table entries

- small hardware device to map virtual addresses to physical addresses without going through page table

- much faster than main memory

- aka associative memory

- has small number of entries, a subset of page tabe entries

- 1-1 correspondence between fields in page table except for virtual page number (not needed)

- small hardware device to map virtual addresses to physical addresses without going through page table

- fields:

- valid: whether entry is in use

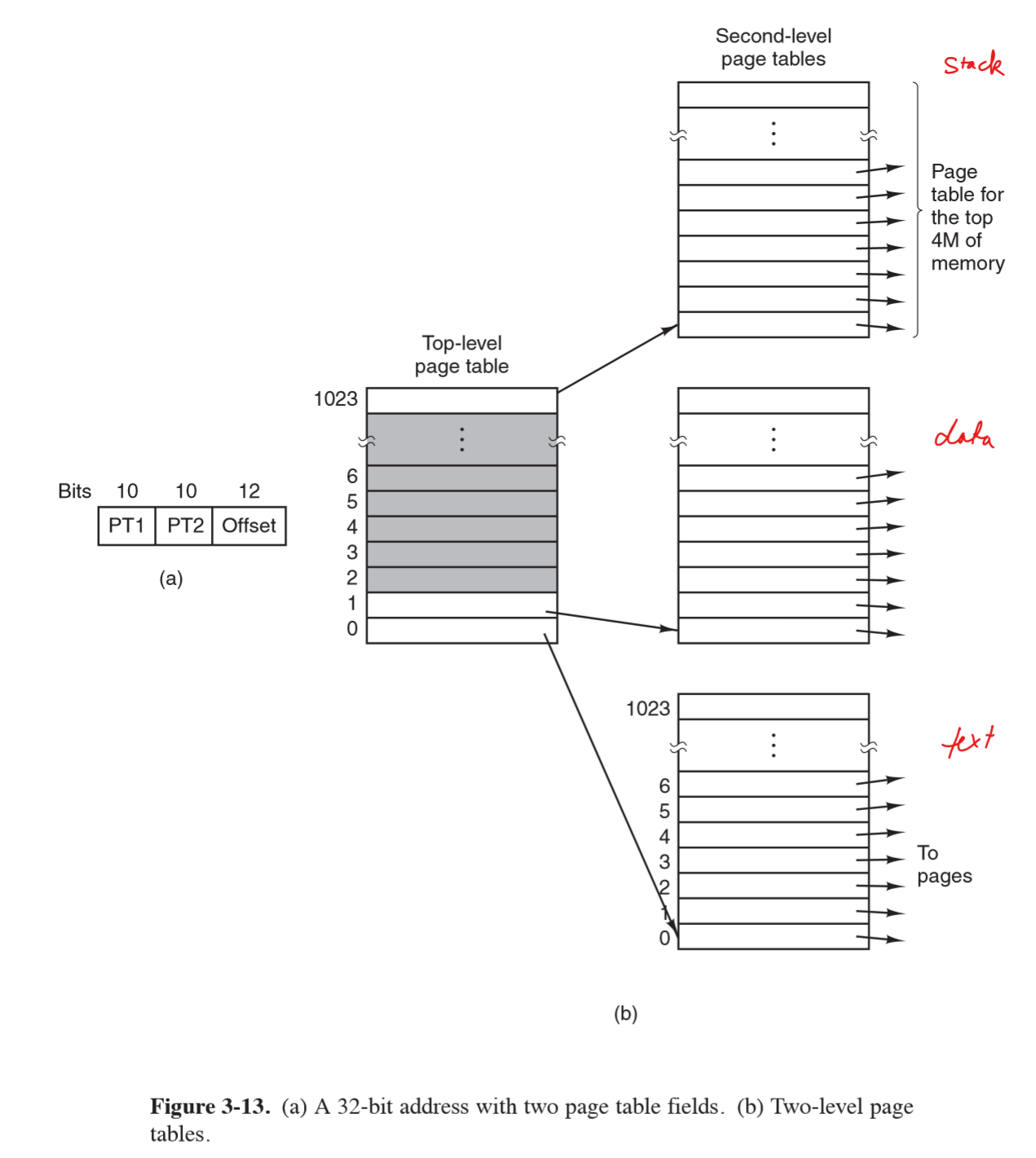

Multilevel page tables

- another way to speed up page table access

- TLB stores frequently accessed entries but still have performance issues if address space of program is large

- key: don’t keep all page tables in memory all the time

- e.g. 32-bit virtual address: 10 bit PT1, 10-bit PT2, 12-bit offset

- 12 bit offset: 4kB pages

- $2^20$ pages (20 address bits)

- PT1 references second-level page table page frame number

- PT2 indexes page frame number for page itself

Memory Replacement Algorithms

- when a page fault occurs and there is not enough free space, you need to decide what

to remove to make space

- local: remove page of same process

- global: remove page of any process

- discard page/write page to disk

Summary

| Algorithm | Comment |

|---|---|

| Optimal | Not implementable, useful benchmark |

| Not recently used | Very crude approximation of LRU |

| FIFO | May throw out heavily used pages |

| Second chance | Big improvement over FIFO |

| Clock | Realistic |

| LRU | Excellent, difficult to implement |

| Not frequently used | Crude approximation of LRU |

| Aging | Efficient approximation of LRU |

| Working set | Expensive to implement |

| WSClock | Good efficient algorithm |

Optimal Page Replacement

- some pages in memory will be referenced in a few instructions, while others won’t be referenced for many instructions

- optimal algorithm removes page that won’t be referenced for the greatest number of instructions

- impossible: operating system has no way of knowing when each page will be next

referenced

- by running a program on a simulator and keeping track of page references, you could implement optimal page replacement on second run

- useful benchmark

Not recently used

- idea: better to remove modified page that hasn’t been referenced in at least one clock tick (~20ms) than clean page in heavy use

- simple, moderately efficient to implement, performance may be adequate

- uses 2 bits of past behaviour

- eviction candidates categorised on values of

R(referenced) andM(modified) bits:- not referenced, not modified: good candidateo

- not referenced, modified

- referenced, not modified

- referenced, modified: poor candidate

- NRU removes page at random from lowest numbered nonempty category

First in first out replacement

- makes no distinction between heavily used pages: poor performance

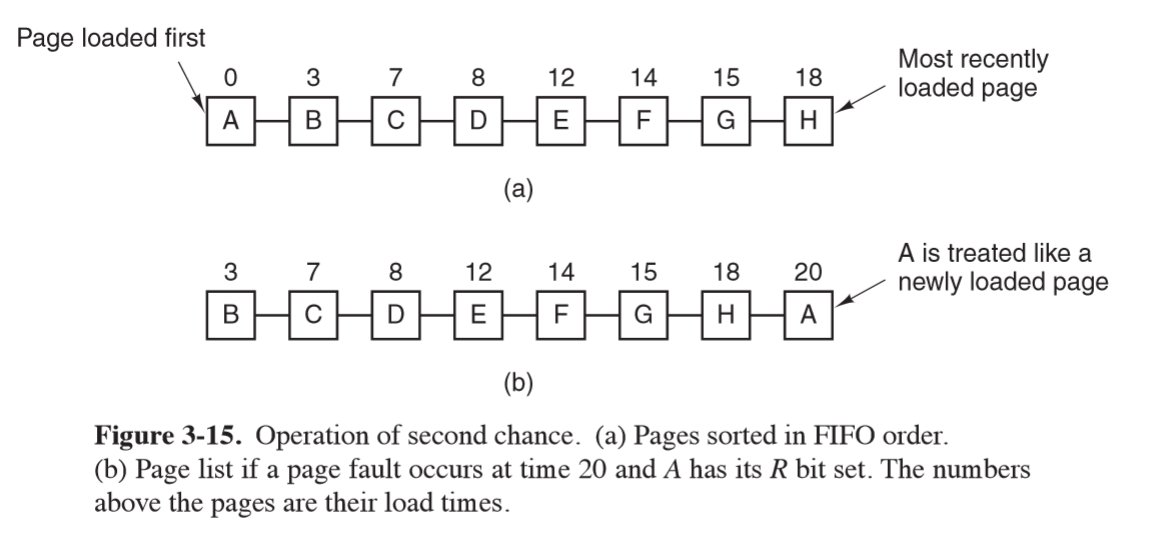

Second Chance algorithm

- pages sorted FIFO but uses referenced bit to avoid throwing out heavily used pages

- if R 0: page at head of queue is both old and unreferenced, so is removed

- if R 1: page at head of queue was referenced, the bit is cleared and it is put on end of the queue

- search proceeds

- inefficient: constantly moving pages around in the list

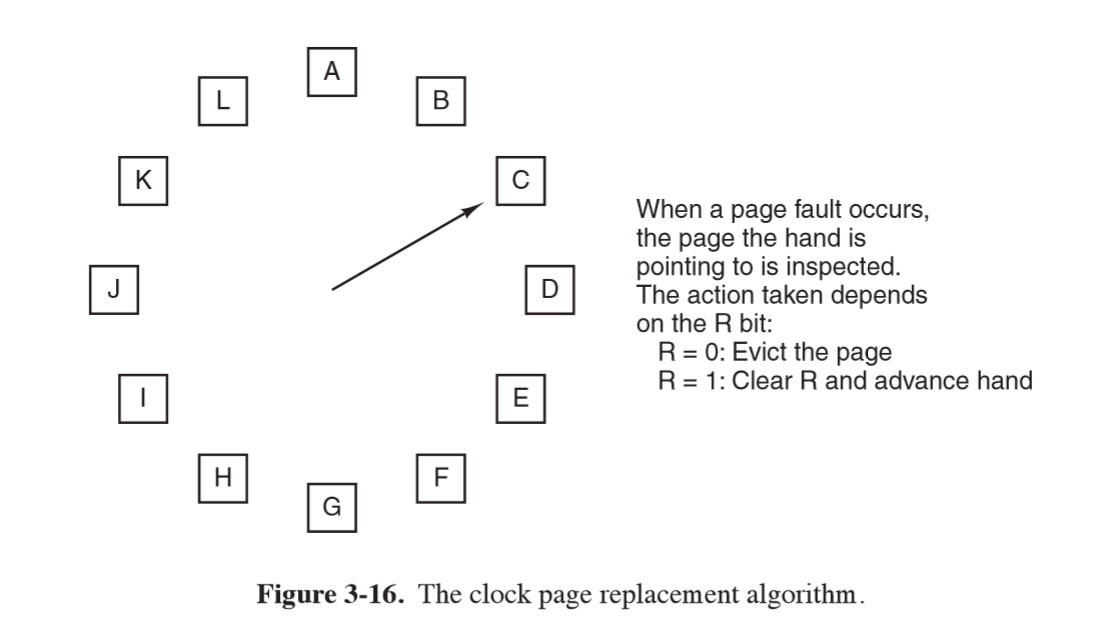

Clock

- overcome inefficiency of second chance algorithm by maintaining circular list

Least Recently Used

- good approximation of optimal algorithm: pages heavily used recently will probably be heavily used soon

- evict pages that have been unused for the longest time

- expensive to implement: linked list of all pages that must be updated on every memory reference

Working Set

- working set: pages currently used by process

- thrashing: frequent page faults resulting from a working set that is too small

- locality of reference: process references only small fraction of pages

- data access is not uniform through memory

- temporal

- spatial

- at a given time, access is clustered around areas

- consecutive code locations

- within data structure

- working set model: approach taken by paging systems to keep track of working sets and ensure it is in memory before process is run

Security

Goal

- secure communication

- authentication

-

confidentiality

- encryption: output ciphertext; hide data from everyone except those holding decryption key

- decryption: output plaintext; recover original data from cipher text using the key

- cryptography

- based on hard problems on average:

- RSA: factorising product of 2 large primes

- AES: substituion-permutation network

- SAT not appropriate: on average can be solved quickly

- based on hard problems on average:

- one-time pad: cannot be cracked. Uses one time pre-shared key of the same size as the message being sent. Plaintext is paired with random secret key

- no perfect security:

- always susceptible to brute force attack

- challenge: make brute force take so long as to be infeasible to perform in lifetime of data

Symmetric cryptography

Encrypt(SecretKey, message) -> ciphertext

Decrypt(SecretKey, ciphertext) -> message

- e.g. AES

- need way to securely exchange secret key

- useful for keeping your own data secure, e.g. full disk encryption

AES: Advanced Encryption Standard

- symmetric block cipher: break data into blocks and encrypt each block

- same plaintext block always produces same ciphertext

- world’s dominant cryptographic cipher

- part of instruction set for some processors e.g. Intel

- 2 de facto variants:

- 128-bit block with 128-bit key,

- 128-bit block with 256-bit key

- key space: $2^{128}$

- hardware support: AES-NI instruction set extension on Intel

ECB: Electronic Code Book mode

- monoalphabetic substitution cipher using big characters (128-bit)

- break plaintext up into 128-bit blocks and encrypt them one after the other

- parallelisable

- easy to attack: can swap cipher blocks without disrupting message integrity

- no diffusion

- may not provide confidentialityX

- shouldn’t be used

- repeated content in same location of ciphertext also helps cryptanalysis

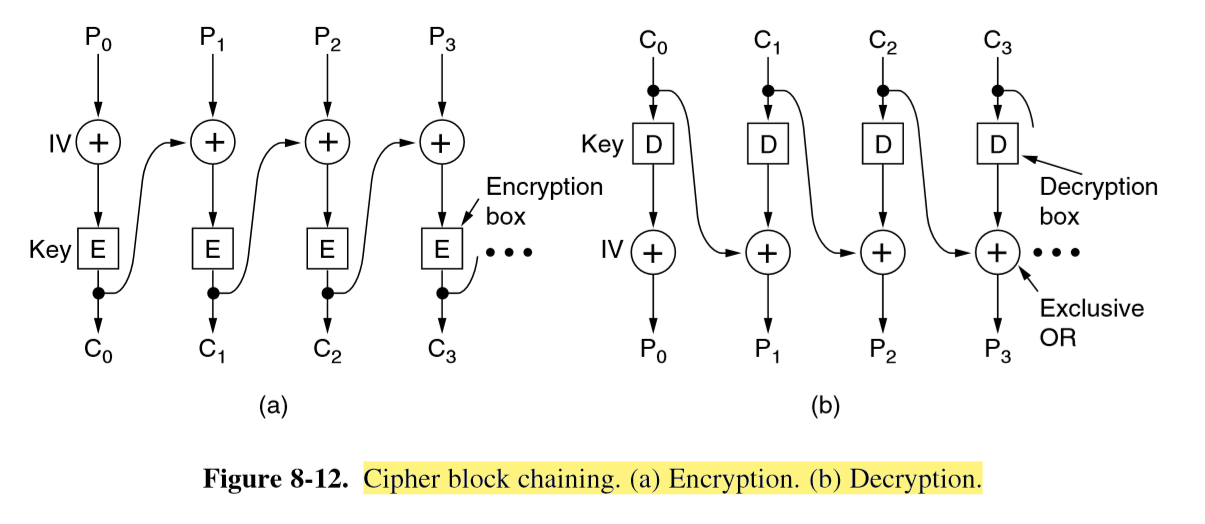

CBC: Cipher Block Chaining mode

- each plaintext block is XORed with previous ciphertext block before being encrypted

- same plaintext no longer maps onto the same ciphertext block, and encryption is no longer big monoalphabetic substitution cipher

- swapping out blocks would produce garbled message, which may hint compromise to the recipient

- initialisation vector: randomly chosen and XORed with the first block

- transmitted in plaintext with ciphertext

- salt: random value added to encryption/hash; public; not to be reused

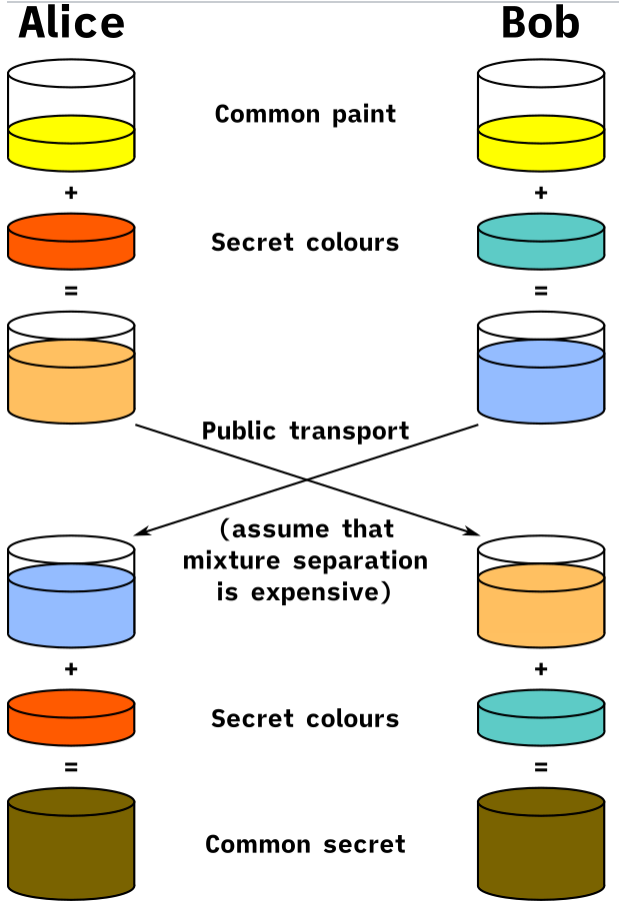

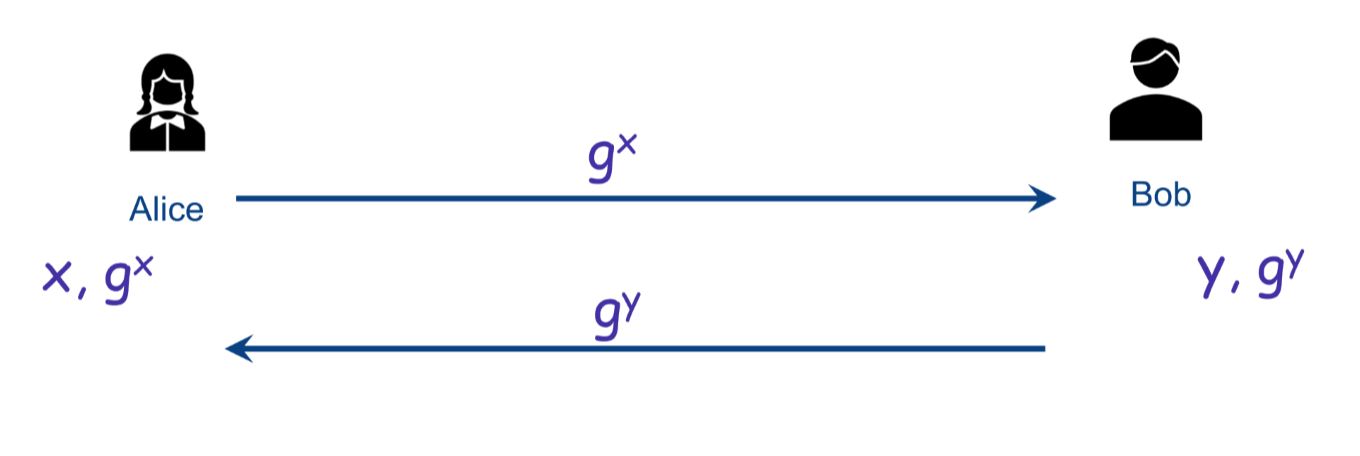

Public Key Cryptography

- aka asymmetric cryptography

- at heart of modern security: Digital signatures, TLS, PGP, Secure messaging, end-to-end encryption

- keyed encryption algorithm, E; keyed decryption algorithm, D

- requirements to make encryption key public

- $D(E(P)) = P$ i.e. if we apply D to encrypted message we get plaintext

- Exceedingly difficult to deduce D from E

- E cannot be broken by chosen plaintext attack

- asymmetric slower than symmetric

- often unsuitable for encrypting large amounts of data

- often used in combination with symmetric cryptography as way of exchanging joint secret key

RSA

- Rivest, Shamir, Adleman

- very secure

- disadvantage: requires keys at least 1024 bits long, so its slow

- mostly used to distribute session keys for symmetric-key algorithms, as too slow to encrypt large volumes of data

- security dependent on difficulty of factoring large numbers

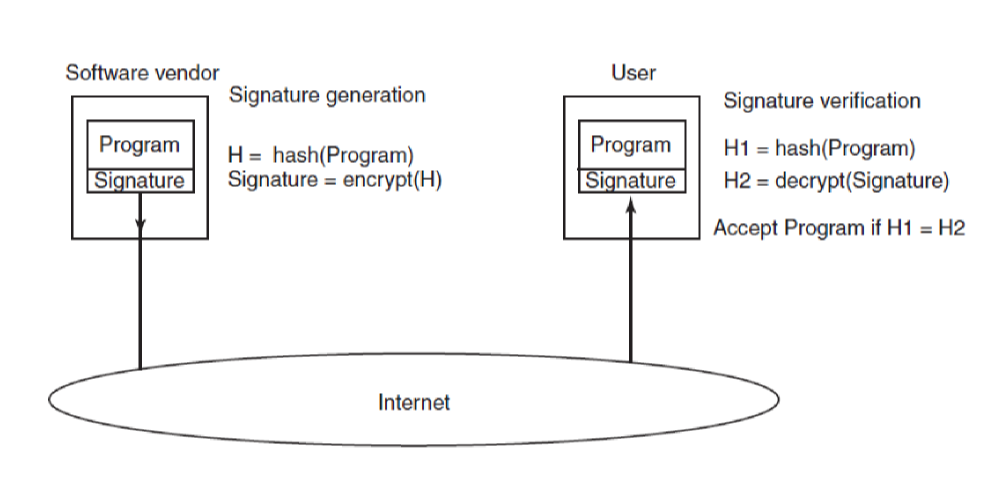

Digital Signatures

- message integrity: message was not tampered with

- message authentication requirements:

- verification: receiver can verify claimed identity of sender: e.g. bank verifying a request for an account transfer

- non-repudiation: sender cannot later repudiate the contents of the message: protect bank against fraud, where someone claims they didn’t authorise a transfer

- receiver cannot have concocted the message themself: prevent bank conducting fraud

Public key approach

- public key would be preferred: you could use symmetric key if there was a central authority everyone could trust, not only to keep track of keys but also to have full access to signed messages

- assume that public-key algorithms also have property $E(D(P)) = P$ (as well as usual properties)

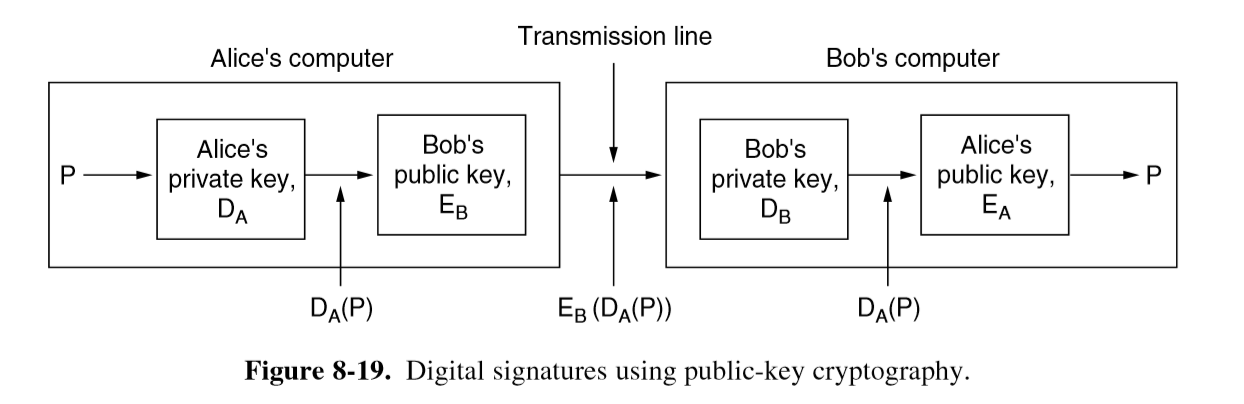

- sender signs with their private key, then encrypts plaintext with recipient’s public key. Recipient decrypts with their private key, then verifies signature with sender’s public key:

- sign with private

SignKey; verify with publicVerifKey

- does this satisfy properties? yes

- verification: yes

- recipient doesn’t know sender’s secret key; the only way for the recipient to have it is if sender sent it

- criticism: coupling of authentication and secrecy

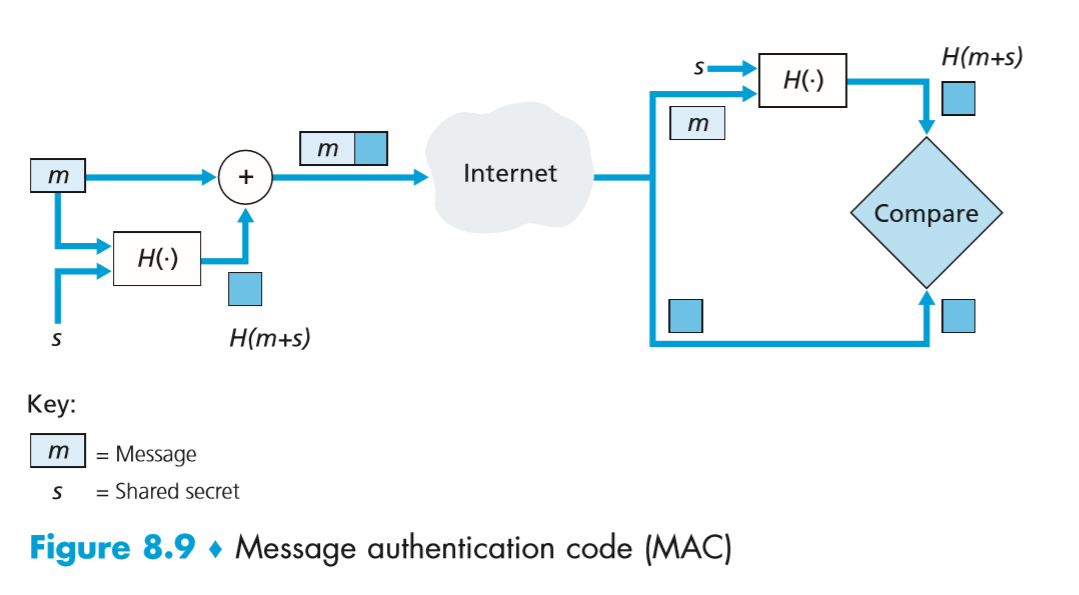

Message Digests

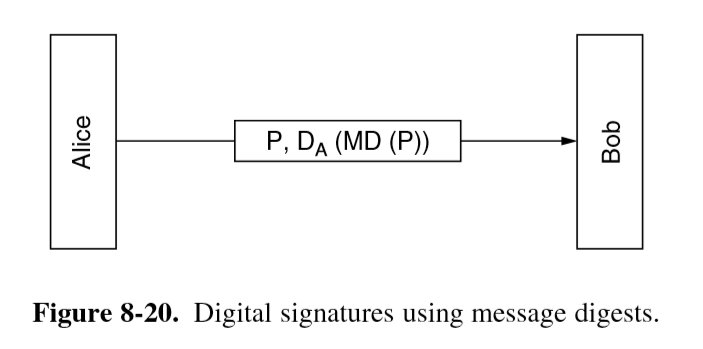

- method that provides authentication but not secrecy

- don’t need to encrypt entire message (i.e. suited to large documents)

- much faster digital signature

- MD: message digest/hash: one-way hash function goes from plaintext to fixed-length bit string

- lossy-compression function

- MD/cryptographic hash properties:

- given P, it is easy to compute MD(P)

- given MD(P), it is effectively impossible to find P

- given P, it is computationally infeasible to find another message P’ such that MD(P’) = MD(P). This requires digest to be > 128 bits long

- change to input of 1 bit produces very different output

- storing password hash is subject to dictionary attack: hash common passwords

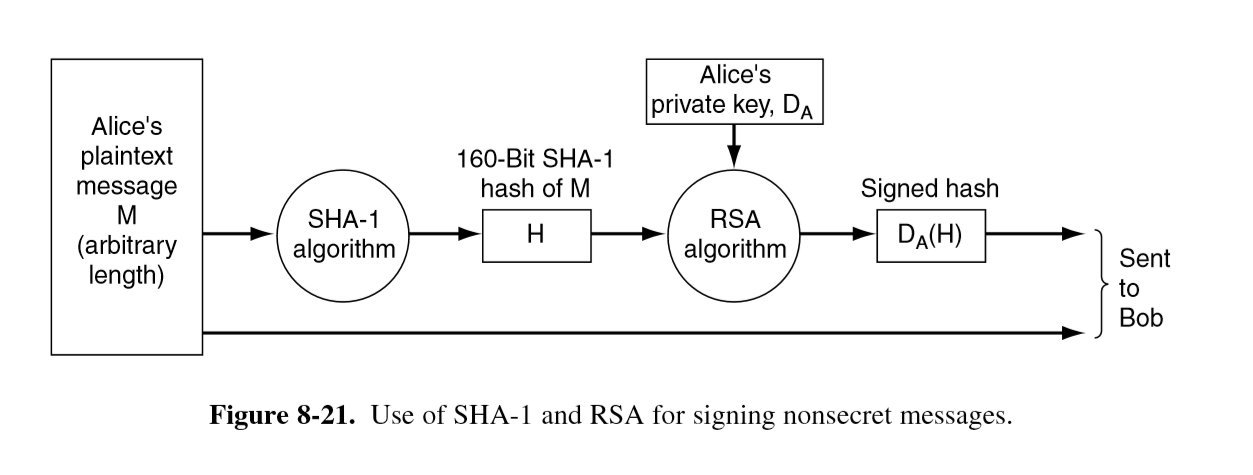

SHA-1

- secure hash algorithm 1

- generates 160-bit message digest

- verification: on receipt Bob computes the SHA-1 hash of the message, then applies Alice’s public key to the signed hash received to extract the SHA-1 Alice sent. If these match, then the message is valid.

- no way for Trudy to modify plaintext in transit or Bob would detect the change

Management of Public Keys

- public-key crypto enables two people who don’t share a common key in advance to communicate securely, as well as enabling authentication without presence of a trusted 3rd party

- signed message digests make it possible to verify integrity easily and securely

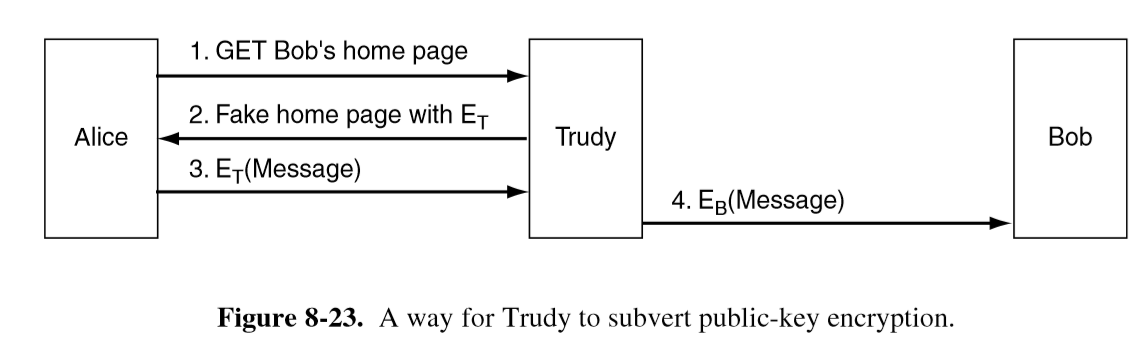

- issue: how to securely communicate your public key?

Certificates

- could conceive of having a single key distribution centre online at all times: not scalable and if it went down all internet security would come to a halt

- CA: certification authority: organisation that certifies public keys

- certificate: binds public key to name of principal (individual/company/…) or attribute

- not secret/protected themselves

- provides proof of identity/ownership

- CA issues a certificate, signing the SHA-1 hash with its private key

- prevent: website spoofing; server impersonation; man in the middle attacks

Alice asks issuer to sign info

d = (PK_alice, Alice)

s = Sign(SK_issuer, d’)

Certificate: Issuer, signature s, d’ = (Issuer, PK_Alice, Alice, …)

Verification: Verify(PK_issuer, d’, s)

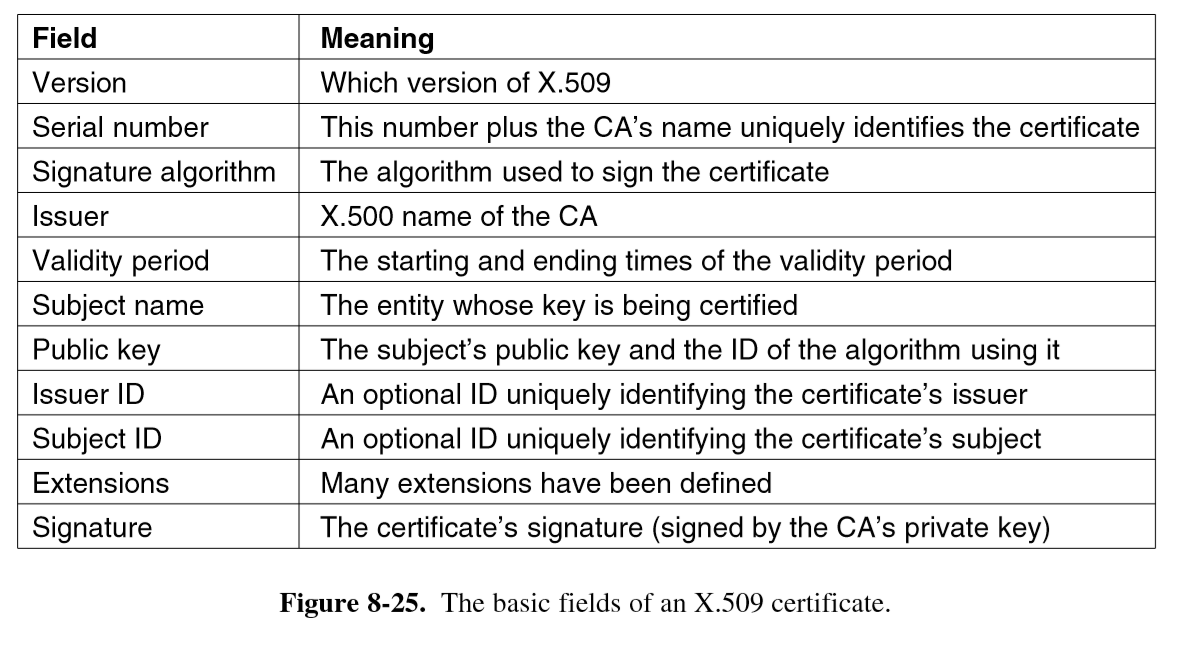

X.509

- certificate standard in widespread use on internet

Fields of X509 certificate:

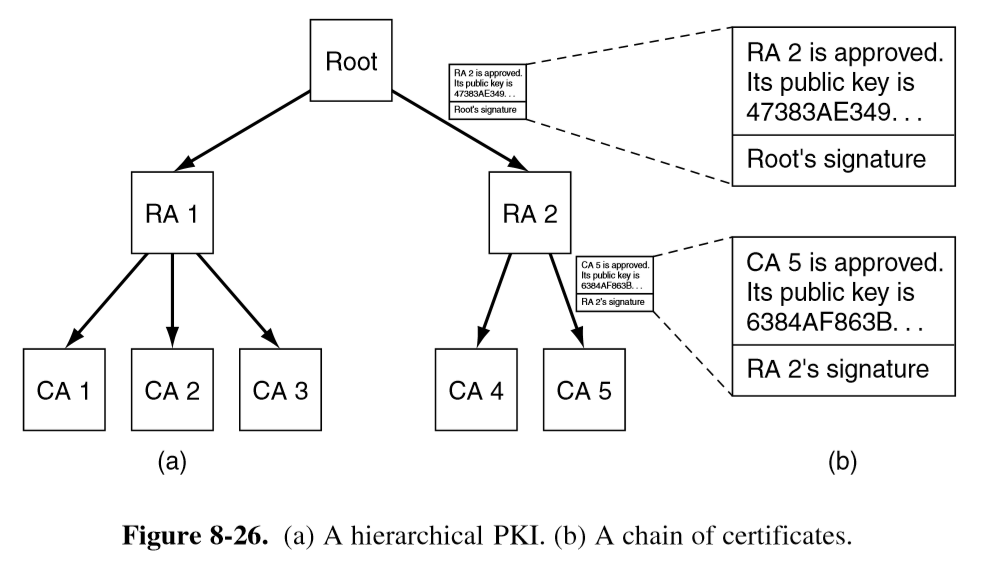

Public key infrastructure

- cannot have single CA: collapse under load, central point of failure

- users, CAs, certificates, directories

- PKI provides way of structuring public key certification, forming a hierarchy

- root: top-level CA that certifies second-level regional CAs

- trust anchor: root public keys are shipped with the browser/system

- regional CAs then certify other CAs which undertake the issuance of X.509 certificates to organisations/individuals

- chain of trust/certification path: chain of verified certificates back to the root

- revocation: each CA periodically issues Certificate Revocation List/CRL

providing serial numbers of all certificates it has revoked (that have not expired)

- if root certificate revoked, all certs below it become untrusted: cross-signing is important

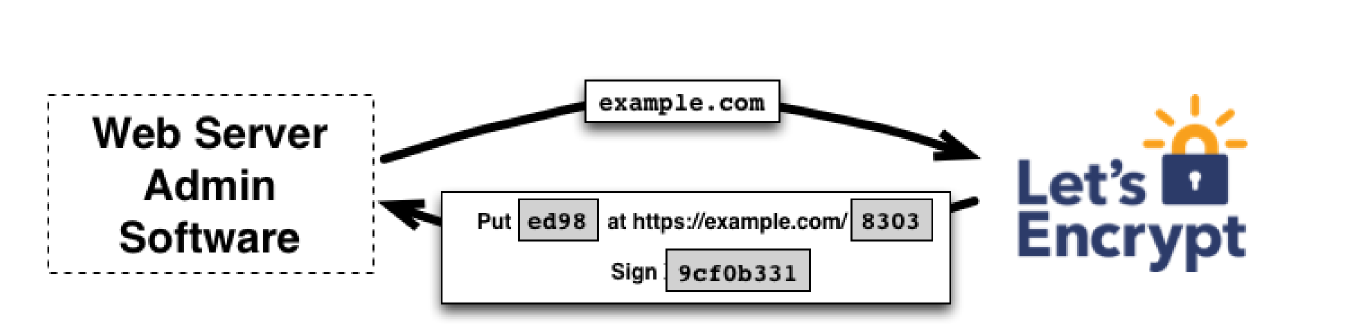

Certificate issuance

- domain validation: most common

- ties cert to domain

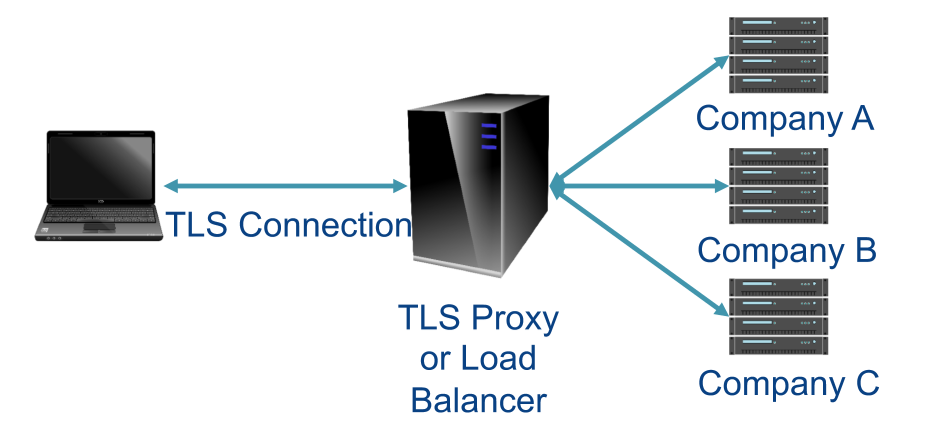

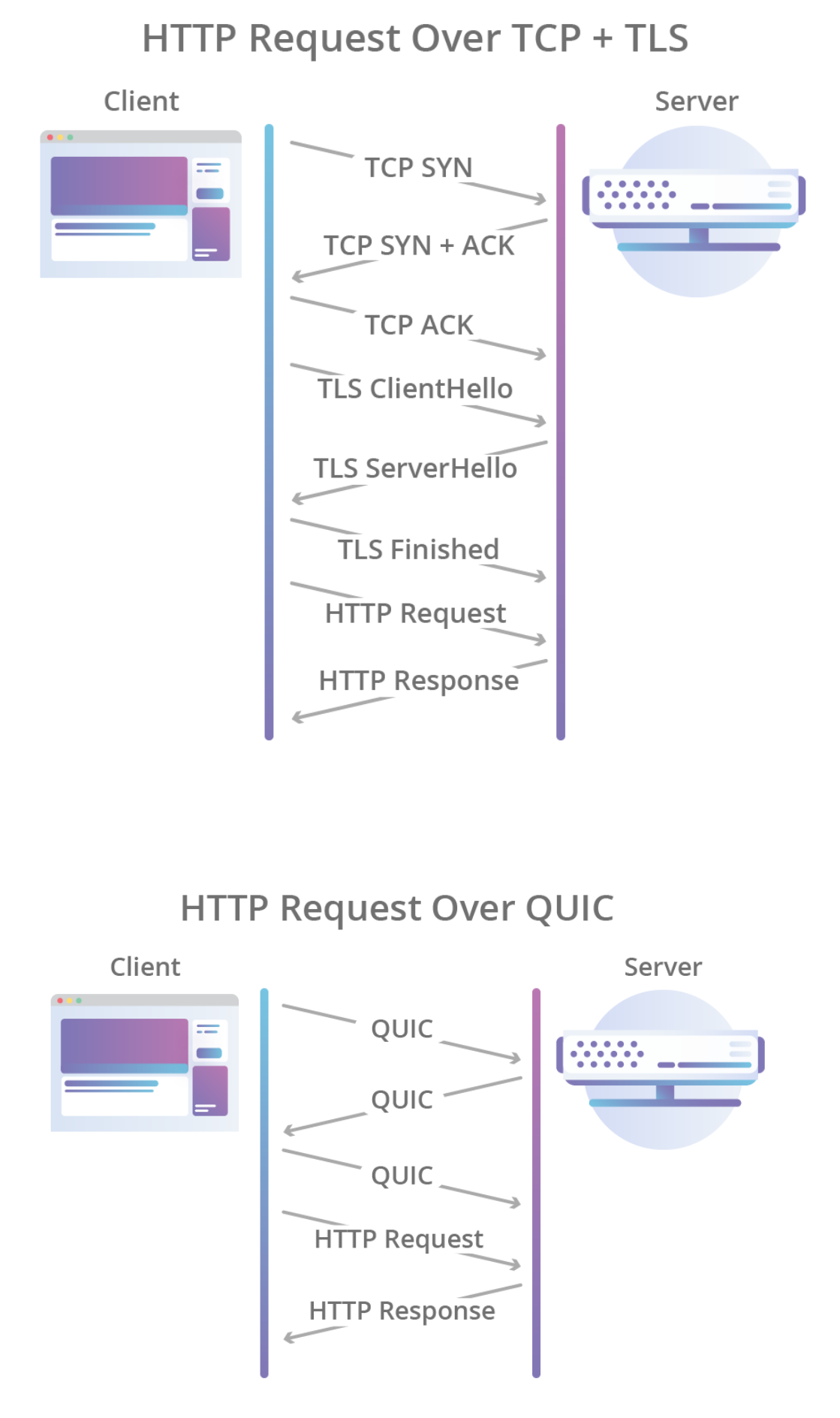

- checks requester has control over the domain